Documentary film now being made about POW Air Force combat pilot

Published in the June 10-23, 2015 issue of Morgan Hill Life

By Marty Cheek

Photo by Marty Cheek

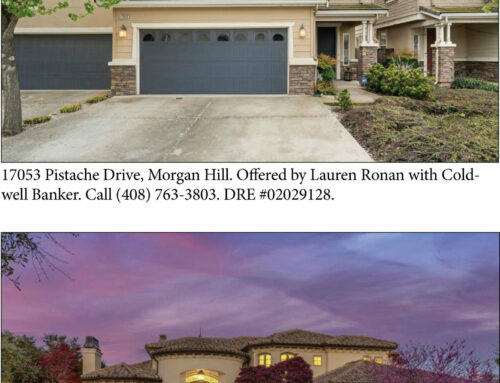

Jeff Grubb displays two photos taken of his father Wilmer Grubb by the North Vietnamese while being held captive during the Vietnam War.

On the night of January 26, 1966, Air Force Lt. Col. Wilmer Newlin “Newk” Grubb followed in his reconnaissance aircraft the Son River on a dangerous mission to photograph a strategic ferry crossing near the village of Son Trach in North Vietnam. That flight would be the combat pilot’s last. Anti-aircraft guns manned by Vietnamese soldiers shot down his plane. Nine days after his capture, the airman was dead.

For decades for his family, many mysteries surrounded the pilot’s death. But in April, Morgan Hill Library supervising librarian Jeff Grubb, along with his brothers Roland, Stephen and Roy, traveled to Vietnam on a two-week trip to discover the story of what really happened to their father. They came at the invitation of a Vietnamese soldier who was part of the unit that downed the pilot’s plane and captured Wilmer. The journey was filmed by independent filmmakers at Napkin Sketch Productions for a documentary called “Fruits of Peace” which has a planned release in 2016.

Grubb was 9 years old in the Philadelphia suburb of Aldan when he received the word about his father. The devastating news hit him, his mother Evelyn and brothers hard.

“He had been a sportsman in his high school and college years,” Grubb recalled. “He loved to play baseball. He was a football hero in high school. He made the scoring run at the end of the season that capped off his career — that kind of thing.”

And Wilmer loved to fly. He joined the U.S. Air Force in the 1950s because he knew from the time he was a young man that he wanted to be a pilot. He flew some of the fastest planes during that era and was one of four Lockheed Starfighter pilots flying one of America’s fastest supersonic jets. Wilmer’s last mission was in a McDonnell RF101C Voodoo, an extremely fast interceptor aircraft loaded with five cameras.

Photo courtesy Jeff Grubb

Wilmer Grubb stands in front his airplane.

The plane flew up the river toward Son Trach and took photos of the ferry crossing. The Americans had already bombed the bridge, but the Vietnamese continued moving supplies across the river by a ferry boat during the cover of night. They hid the ferry in a large cave during the day. The Americans wanted to see what kind of activity was happening at that strategic point, and sent Wilmer and a second plane to serve as his wing-man.

“The Vietnamese gunners saw him coming and got him in their sites and hit his aircraft right as he was beginning to go up,” Grubb said. “The plane exploded and he ejected immediately. He radioed his wing-man. The other aircraft was up high, so they didn’t get him… The gunners said they knew it was a scout plane because all the reels of film came raining out of the sky.”

Wilmer parachuted down into the third ridge of mountains near the village. Soldier soon captured him and he was taken to a home in the village where his wounds were tended. From there, Wilmer’s last days fell into uncertainty.

“For my family, it’s always been a mystery,” Grubb said. “We knew he was shot down and for a while he was in a missing-in-action status. Photos were released so we knew he had been taken prisoner and his official status was changed to prisoner of war. But then at the end of the war, we were told that he died nine days after he was captured. And we were told he died of wounds he received in the crash. But during our meetings with these Vietnamese in the anti-aircraft unit, which included the soldiers who captured my father, they all said that he had scratches on his knee which were treated by a local medic. He did not have life-threatening injuries from the crash. So it’s still a mystery to us what caused his death.”

The Grubbs were contacted by Du Pham Duc, the historian of the C-4 anti-aircraft unit that shot down Wilmer’s plane. Du Pham Duc was not a member of the unit when the shoot-down happened, but the unit was very active throughout the Vietnam War. They fought for the North Vietnamese throughout the war and shot down many American aircraft and gained fame. Wilmer’s plane was the first aircraft that they shot down, so they had a lot of memories of the day he was shot down and how he was captured, Grubb said.

Photo courtesy Jeff Grubb

A North Vietnamese propaganda photo Wilmer Grubb as a prisoner of war.

The Grubbs’ Vietnam trip started in Ho Chi Minh City, also known as Saigon, where they were given a tour of the apartment building where Wilmer was billeted. The building will soon be torn down for a high-rise, but the Grubbs were able to locate Wilmer’s apartment based on a photograph.

The next step was to Quảng Bình Province where they traveled to the village of Son Trach. The visit gave new perspective to Grubb for what happened to his father. The brothers were shown where the plane went down and broke into two parts. The wreckage was long gone, the metal collected by villagers.

“It’s almost fifty years since the shoot-down and we saw craters from bombs that are still in that area,” Grubb said “We were able to walk the river and see the mountain top where my father’s parachute came down. We were able to envision clearly what it was like because the weather was similar to what it was like when the aircraft was shot down. Kind of low cloud cover where the aircraft would have been flying low and then would have gone back up above the clouds. It really brought a real human geography to us, rather than imagining what it was like. I could feel the ground under my feet and talk to the people who had been there that night.”

The Grubbs were shown the house where Wilmer was first taken. The woman who had tended to Wilmer recalled the experience of meeting the captured American pilot. There were concerns that if other villagers knew about him, they might attack him because of their anger toward the United States.

Photo courtesy Jeff Grubb

Jeff Grubb, second from the left, and part of his extended family, visit with some of the Vietnamese who were involved with the anti-aircraft unit that shot down his father.

“She talked about feeding him. And her husband gave him a beer,” Grubb said. “And we talked to the political commander who talked about speaking to my father in Russian. My father was based in Europe before Vietnam so he had to learn to speak some Russian, so there was some communication.”

The political commanded confirmed to the Grubbs that their father had been transferred from his custody and taken directly to Hanoi. The next stage of the trip brought the brothers to the Hỏa Lò Prison, known also as the “Hanoi Hilton.” Although there is no evidence or documentation that Wilmer was actually here, this is the location where Grubb and his brothers believe their father died, and they paid their respects to his memory during the visit. The Vietnamese listed Wilmer’s date of death as Feb. 4, 1966. The Air Force pilot was buried in 1974 in Arlington National Cemetery.

When Grubb first heard about the invitation to visit Vietnam and meet the people who were with his father during the last days, he felt uncertain about going. They were the people who had changed his life forever, he said.

“One of my take-aways from this whole trip is that times do change and people can change over time. I was kind of fearful going in,” he said. “I didn’t know what the people would be like, but I found that the people were open and welcoming, that they honored my brothers and me for honoring my father by trying to find out what happened to him.”

He also saw that even though it is still a communist-controlled country, Vietnam is quickly absorbing western culture and entrepreneurship. Near Vietnamese flags flying the hammer and sickle stand American businesses such as Pizza Hut, KFC and Starbuck’s. Fifty years can change a land — and the people in it. Time brings reconciliation.

“I find the people were very kind and understanding of our tragedy,” Grubb said. “For my family, it was a tragedy, and for their military outfit it was a great victory. These are aging soldiers who did their duty as I would have if my country was being attacked. And they have gone on to be educators and farmers and businessmen.”