Published in the December 11-25 issue of Morgan Hill Life

By Marty Cheek

Marty Cheek

An ancient Roman would nod in recognition if he should somehow happen to visit our 21st-century South Valley world and see many of the holiday festivities enjoyed by residents of our community. That guest from another age would understand why Dec. 25 is celebrated by more than two billion people around the world as the birth date of the “Son of God.” More than two thousand years ago that date was celebrated in the Roman world as Dies Natalis of Sol Victus, “the Day of Birth of the Unconquerable Sun.”

I’d love to time-transport the early fifth century Roman writer Macrobius Ambrosius Theodosius to Morgan Hill and introduce him to the modern-day winter holiday season we are now celebrating with so much feasting and fun. Macrobius would be the perfect citizen of Rome to invite to our time because much of what we know about how the Romans celebrated their own winter holiday season was penned in the ancient author’s Saturnalia, a compendium of the customs of ancient Roman religious customs and antiquarian traditions. Ancient Rome’s Saturnalia holiday season lasted a little more than a week, from Dec. 17 to Dec. 25, the last day of the year according to the Julian calendar.

Mr. Macrobius, I would tell him, we have you Romans beat. We don’t celebrate the winter holiday season for just a single week. We party-hearty for a whole month. In the United States, the holidays start on the fourth Thursday of November, a day of gratitude to whatever deity we might worship. Macrobius would see the significance of family members and friends gathering together for the communal consumption of a sacrificial turkey bird, stuffed with bread and placed in an altar-like oven to roast at 300 degrees.

He’d be keen to observe that following the Thanksgiving dinner, we have a traditional gathering of everyone around the wide-screen television set, an electronic window of mystical technological powers enabling American mortals to witness from the comfort of our living room couches the ceremonial battle of two tribes fighting for territory on a pastoral field 100 yards long. Our American gridiron gladiators in combat for possession of an oddly shape ball most likely won’t lead to the violent deaths of players in front of thousands of spectators. But it might cause Macrobius to comment that the crowds of his own day loved violent sports too, gathering in the Colosseum and other arenas of the ancient Mediterranean world to witness lives and limbs lost in bloody combat.

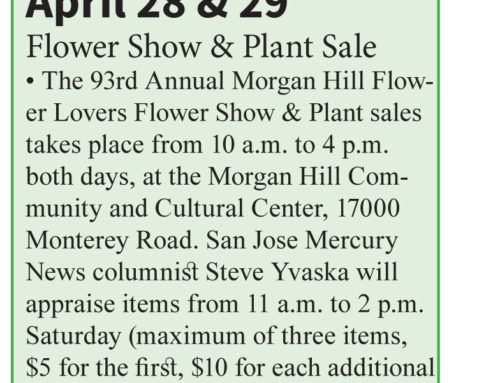

Another holiday custom we follow in our modern world is to spend the day after Thanksgiving at the temples of commerce we call shopping centers and malls. Macrobius would see the significance of our quest for holiday gift goods which we can take into our ownership simply by paying homage to the gods of mercantilism — Am-Ex, MasterCard, and Visa — with the ceremonial swiping of our plastic tokens through a credit card reader. Macrobius would appreciate our quaint Black Friday customs, commenting that during Saturnalia, the people of the Roman Empire would also give gifts to one another. The Roman day of gift giving was Dec. 23, a date on their calendar year they called “Sigillaria.” Children would receive toys, adults would receive the Roman equivalent of gag gifts. Other items Romans presented to each other included dice for gambling, perfumes, books, writing tablets, axes and hunting knives. Personally-written poems were attached to the gifts to show the presenter’s affection for the recipient.

During the holiday season, Macrobius would note the importance of candles and decorative Christmas lights in our celebration. Saturnalia, he would comment, was considered by Romans a festival of light to cast aside the darkness of the winter solstice. The festival was also celebrated with an abundance of burning candles, symbolizing that through the light of knowledge and truth we cast aside the darkness of ignorance and falsehoods.

Bringing a close to our month-long season of celebration, I would take Macrobius to a New Year’s Eve party where, with the televised count down dropping of a large glowing ball in New York’s Time Square at the midnight hour, champagne-drinking revelers usher out the old year and welcome in the new one. The Roman gentleman would comment that little has really changed over the centuries. He would describe the festival of Janus on Jan. 1, the day following Saturnalia, explaining how the Romans celebrated their own new year with a party honoring their god of gateways. Janus bore two faces, one looking back toward the past and the other looking toward the future. Indeed, the month of January still carries the name the Romans gave it in commemoration of Janus.

Human nature hardly really changes over the centuries. And Macrobius would no doubt appreciate how the customs and traditions of our modern world parallels the winter holiday religious rites he and other Romans followed during the celebration of Saturnalia.