The declaration lets agency work with cities and county to launch regulations and restrictions

![]()

By Marty Cheek

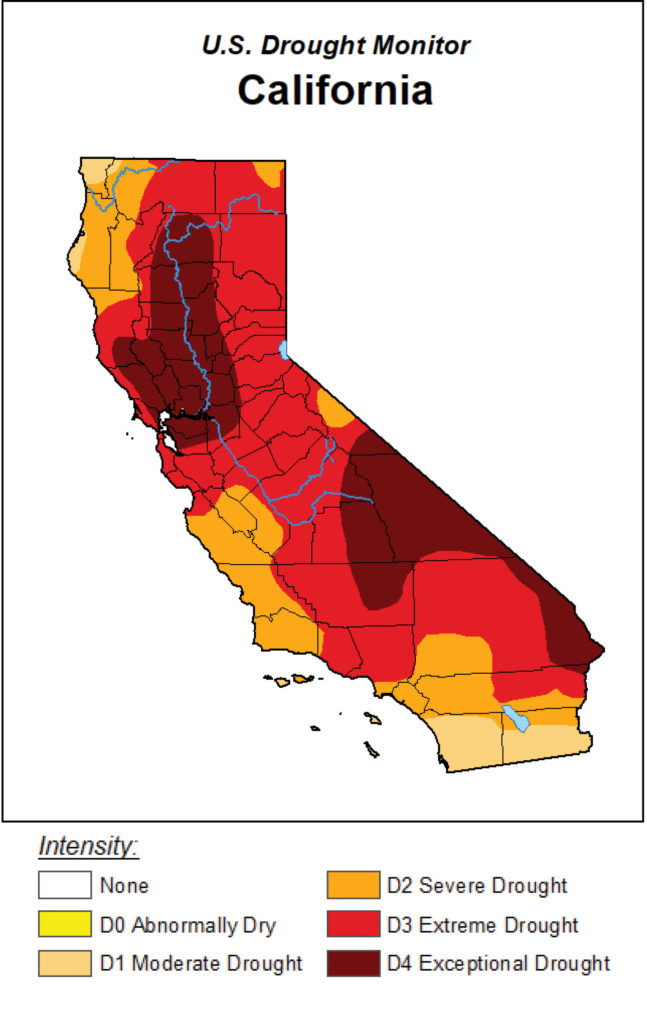

Get ready for a summer of brown lawns and short showers.

With the extreme drought reducing the supply of H-2-0 for all of California, Valley Water Board of Directors voted June 9 to declare a water shortage emergency condition in Santa Clara County. They also urged the Santa Clara County Board of Supervisors to proclaim a local emergency.

The action implements a 15 percent mandatory water use reduction from 2019 levels. In the previous drought, Valley Water mandated water usage to drop 25 percent from 2013 levels.

The action implements a 15 percent mandatory water use reduction from 2019 levels. In the previous drought, Valley Water mandated water usage to drop 25 percent from 2013 levels.

The declaration lets Valley Water work with cities and the county to launch regulations and restrictions on how water is delivered and consumed.

“This is an emergency,” Valley Water CEO Rick Callender said in a press release. “Our water supplies are in serious jeopardy. Valley Water will protect our groundwater resources by all reasonable means necessary and ensure we can provide safe, clean water to Santa Clara County. Every drop of water saved is a drop we can use in the future.”

The dramatic action to declare an emergency comes on the heels of the second driest back-to-back winter seasons on record. The drought has forced drastic reductions to Valley Water’s allocations of imported water from the State Water Project and Central Valley Project.

Valley Water staff have been working on withdrawing previously stored water supplies from its out-of-county groundwater bank near Bakersfield and purchasing emergency water from its partners.

But those supplies are not guaranteed. The drought has increased competition for a limited supply from other retailers throughout the state, raising the price of water from about $200 an acre-foot to as much as $2,000 an acre-foot, said Valley Water Vice Chairperson Gary Kremen.

“We’re having trouble buying water on the open market because everyone else is buying it at the same time,” he said. “The price is about 10 times what it was two years ago.”

Snow-melt runoff in the Sierras reaching the Delta region of California has been significantly reduced because of the drought, adding to the state’s water woes, he said.

Snow-melt runoff in the Sierras reaching the Delta region of California has been significantly reduced because of the drought, adding to the state’s water woes, he said.

“It was so dry last year that the water went right into the ground and it didn’t really flow into the reservoirs and rivers,” he said.

Adding to the county’s local water supply challenges, Anderson Reservoir was drained to 3 percent capacity starting last fall under the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission’s order for public safety.

Geologists warned the dam structure might fail if a major earthquake occurred along the fault running under the lake. It is expected to remain nearly empty for at least a decade as construction proceeds with a seismic retrofit of the dam.

A water shortage emergency condition declaration is one of the strongest actions available under law to the Valley Water. It underscores the need to protect local water supplies for public health and safety and avoid the severe consequences of subsidence if aquifers are depleted and if reservoirs and other supplies can’t sustain the county’s water needs. That’s why Valley Water staff recommended the 15 percent water use reduction.

A water shortage emergency condition declaration is one of the strongest actions available under law to the Valley Water. It underscores the need to protect local water supplies for public health and safety and avoid the severe consequences of subsidence if aquifers are depleted and if reservoirs and other supplies can’t sustain the county’s water needs. That’s why Valley Water staff recommended the 15 percent water use reduction.

“If we don’t achieve our goals, if we can’t get water transferred into the county, if we can’t get any water on the open market, there are options,” Kremen said. “We might borrow some from adjacent water districts.”

Another year of drought will increase the challenges of finding water to sustain two million people living in Santa Clara County as well as Silicon Valley industries and the South Valley’s ag businesses.

“It could be pretty draconian next year,” Kremen said. “We can see what the emergency will be next year and we want to make sure there is some water in the ground, some carry-over water for next year, especially with wildfires, they can be pretty bad.”

Farms in the South Valley are preparing for a reduction in their water supplies, he said.

“The good news is that our crop growers in the southern part of our county are some of the best water conservers in agriculture in the state,” he said. “They’ve done a lot of things already, which is phenomenal. Most growers understand that water is a cost of their product so it goes right to their bottom line if they use less water.”

However, if next winter and spring bring too little rain, the year 2022 will be dire for farmers. Row croppers might not plant, he said.

Valley Water hopes Gov. Gavin Newsom will add Santa Clara County to the 41 counties now under a drought state of emergency because this will open up access to federal aid. About 30 percent of the state’s population live in these counties.

“With the reality of climate change abundantly clear in California, we’re taking urgent action to address acute water supply shortfalls in northern and central California while also building our water resilience to safeguard communities in the decades ahead,” Newsom said in a press release.