Remains of Gilroyan Frank Masoni identified with dental records, X-rays

Published in the November 22 – December 5, 2017 issue of Morgan Hill Life

Photo by Marty Cheek

Clorinda Sergi, left, and her sister, Lanna Sandoval, with pictures of their uncle Frank Masoni.

After 74 years, Frank Louis Masoni came home from the war. His remains were laid to rest with a military funeral at Gavilan Hills Memorial Park Nov. 18.

Born in a farmhouse on Rucker Avenue Oct. 29, 1922, the last time the Gilroy man saw his hometown was from a Greyhound bus taking him back to his Marine unit. He enlisted in 1942 after Pearl Harbor. Following his boot camp training in San Diego, he returned to Gilroy on furlough to spend family time with his Italian immigrant parents, Clorinda and Salvatore, as well as his three younger brothers, Louis, Salvatore and Richard.

At the end of the visit, Richard, then 16, took his 20-year-old brother to the downtown bus depot.

“They said their goodbyes and Frank went off to service,” said Lanna Sandoval, Richard’s daughter. “My dad being so young at the time never realized it could have been the last time he saw him. He never knew at that moment. And they said ‘bye, and he thought he’d see him when he got back.”

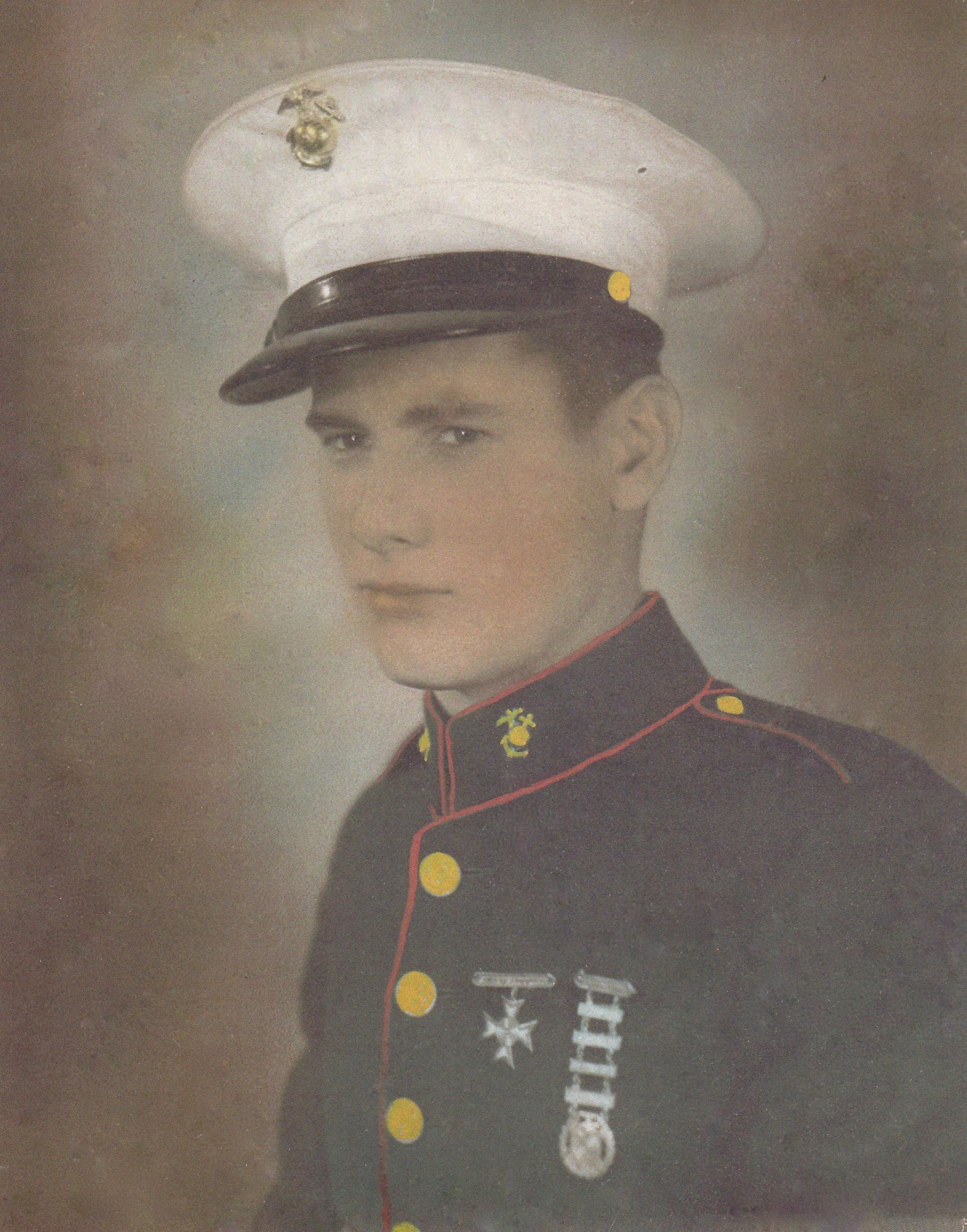

Frank Masoni in 1942.

Photo courtesy Masoni family

Masoni attended Rucker Elementary School, St. Mary’s School and graduated from Gilroy High School. He stood 6-foot and had been a good athlete, a hurdler on the track team. He and his brothers worked hard during the Great Depression picking prunes in the local orchards and other farm labor. He gained gun skills shooting birds that ate the fruit in the orchards. After graduation, Masoni found a job working at the Pollyanna Bakery, delivering bread during the day to Gilroy businesses and residents until he was promoted to night baker. That experience no doubt helped him find a Marine job working as an assistant cook on a ship. A pocket-sized journal he had kept recipes in during the war includes one for spice cake that served 300 men.

As part of the 2nd Marine Division, Masoni found himself in the fall of 1943 with 18,000 other men in the amphibious landing of the Tarawa Atoll located in the central Pacific Ocean. About 4,500 Japanese defenders waited for the American invasion forces. The Battle of Tarawa raged from Nov. 20 to Nov. 23. Masoni, who had earned a sharp-shooters medal from the Marines, made his way through the coral reef and found himself on the beach on the second day of the fight. No one knows how he died that day. He was one of 1,009 Marines killed. The men’s remains were buried in the sand, with the intention by the military to return after the war and give them proper burials.

Photo courtesy Masoni Family

Medals awarded to Frank Masoni.

Because his body did not have a dog-tag, the military couldn’t properly identify him. With other unknown American military men, his bones were buried in National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific in Honolulu. During the next seven and a half decades his family wondered where their beloved son and sibling ended up. They believed he might have been buried at sea or the remains were back on the beach in Tarawa.

“We had no idea what the circumstances were,” Sandoval said. “My dad always said Uncle Frank died in action in World War II in the battle of Tarawa, but we didn’t know much more than that. He was just never recovered.”

In August, the family learned the Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency confirmed Masoni’s remains. In September, they met with military personnel who provided documentation with details of the Marine’s experience during the fierce battle.

“Last year some forensic scientist with the government figured out, hey, I can identify these bodies,” said Clorinda Sergi, Richard’s daughter. “They did it with dental records, and with X-rays. When you go into the Marines and do all those physicals and everything, they take X-rays. They superimposed the X-rays over the bones. They then positively identified him through dental.

Some family members had gone to the cemetery in Honolulu to see Masoni’s name on the remembrance wall. They took photos of the wall, never realizing that he was nearby in an unmarked grave, Sergi said.

For Masoni’s family the funeral was a reunion celebrating the Marine’s return to his Gilroy home, Sergi said.

“It’s really nice to have closure and find out what really happened,” she said. “I think my dad, Richard, is really happy he’s coming home.”

A bittersweet part of the story is that Masoni’s mother never saw this homecoming. For many years after the war, she wrote polite but determined letters asking the military to not to give up on bringing back his remains. One dated Dec. 29, 1945, addressed to the General Accounting Office in Washington, D.C., expressed her plea:

“Dear Sir: Only a few lines to remind you that I am still interested in having the body of my son Frank L. Masoni sent home to me. Claim No. 1316181. Sincerely, Mrs. Clorinda Masoni.”