Published in the April 25 – May 8, 2018 issue of Morgan Hill Life

By George Fohner

George Fohner

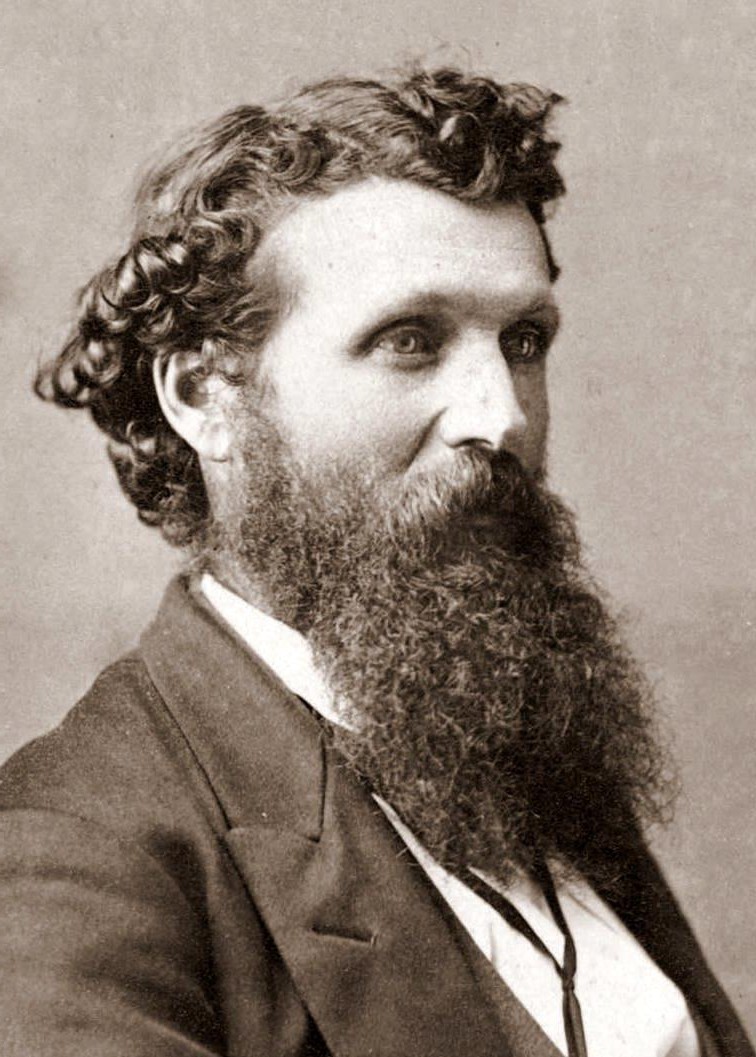

John Muir

One hundred and fifty years ago this month, John Muir arrived in California for the first time and began his storied walk from Oakland to Gilroy, over Pacheco Pass, and on to Yosemite. Already well traveled in the wilds of North American by the time of his arrival in California at the age of 30, Muir would go on to become the patron saint of the conservation movement, forever associated with the Sierra Nevada and the conservation of wild places.

As Muir moved south of San Jose into the southern Santa Clara Valley on that walk to Yosemite, he was completely enthralled with his surroundings. He likened the fresh, springtime air spiced with fragrance of wildflowers to the “breath of angels,” calling it the most invigorating he had ever experienced. Muir marveled at the redwoods that cloaked the mountains to the west and mix of oaks and grasses to the east while he wandered through rich bottomlands that glowed with vast expanses of wildflowers of white, yellow, and purple, sparkling with highlights of red and blue in a tapestry with vivid green grasses. Muir equated his experience traveling through the southern Santa Clara Valley to a baptism that awakened in him a new capacity for happiness.

Exhilarated as he was about the natural wonders around him and captivated by the novelty and beauty of the California landscape, Muir in his writings about the trip barely mentions the names of the communities he passed through. He does mention Gilroy, however, because it was there he turned east to on his way to the pass. Gilroy in 1868 was becoming a regional center for a diverse mix of agriculture, logging, and other enterprises, and was a key part of the Miller & Lux livestock empire that shaped California agriculture.

If Muir spent time in Gilroy, he might well have encountered William Hanna, a leading citizen at the time and for many years thereafter. Hanna was a councilman when Gilroy incorporated as a city in 1870, later becoming mayor.

Muir’s enthusiasm for his surroundings did not diminish as he headed east from Gilroy toward Pacheco Pass. Regaled with “shouts” of quail and the song of streams cascading into valley, Muir frequently departed the road to explore the “rich garden” on sunlit hillsides, in shady, fern-filled grottos, and in the cobble streambed where Pacheco Creek meandered back and forth in the midst of sycamore, alder, and dogwood.

Like Muir, Henry Miller recognized the rare value of the southern Santa Clara Valley. Of the million and a half acres Miller owned, and the vastly larger area he controlled by lease or other means in valleys and mountains throughout the west, he favored the Gilroy area as his business headquarters, home, and vacation retreat. He referred to his Bloomfield Ranch just south of the city of Gilroy as the “center place,” reflecting both its importance to his business as well as its geographic location.

Miller’s life revolved around work, but he treasured spending Sundays and his brief vacations with family on his land at Mount Madonna, and took great pleasure in hosting employees and business associates there.

John Muir and Henry Miller are not generally thought of as having similar perspectives on the environment or its use, but they both clearly considered the southern Santa Clara Valley a special place. Both also were in fact similarly frugal and conscious about using natural resources wisely and not squandering them.

The 150th anniversary of Muir’s arrival in California and his walk through Santa Clara Valley comes at a time when land use decisions affecting South Valley communities are being made under intense budgetary and development pressure. Both Muir and Miller undoubtedly would agree that current residents of the area and their elected representatives should not undervalue this extraordinary area as they make decisions that will affect the quality of life far into the future.

George Fohner has lived and worked in Gilroy for 34 years.