If this story has the chance to give someone a way out from going the route of suicide, veterans is happy to tell it.

![]()

Editor’s note: This column discusses thoughts of suicide and substance abuse.

By Connor Quinn

Connor Quinn

“Why didn’t you call me?” It’s a phrase I’ve heard multiple times in the past couple of months. People who care about me ask why I didn’t reach out before I got to a very dark place and almost ended my life. It’s a question I’ve asked about a lot of different people that I’ve known from my time in the U.S. Army.

“Why didn’t you call me?” It’s a phrase I’ve heard multiple times in the past couple of months. People who care about me ask why I didn’t reach out before I got to a very dark place and almost ended my life. It’s a question I’ve asked about a lot of different people that I’ve known from my time in the U.S. Army.

As a medic I was responsible for my guys in Afghanistan’s health and welfare and that feeling never really went away. The tragedy is that I’ve lost more friends to suicide than I lost in combat. It seems every few months I hear about someone I was deployed with ended up losing their battle at home. My personal tragedy is that I was almost one of them.

So why didn’t I call? Why didn’t I reach out? Well, I think the answer is that I was trained to not show those emotions, that I needed to bury my empathy in order to complete the task at hand.

Self-care was not a priority of mine in my nine-year career and it carried over to my present day. The feelings I had buried and poured alcohol on for a decade decided that they had stayed down there long enough. When Afghanistan fell and I watched the Taliban take over Kabul, I had a reaction to it.

It was short lived, and I had my own life to get back to and people I needed to take care of at home. I couldn’t let that pain and feeling of betrayal interfere with the work I was doing, so I buried it right next to all those other bad memories I have from my tours overseas.

Looking back I can see the warning signs. About Christmas time I started drinking more and more. I used to at least take the weekdays off but, I got to the point that I was drinking daily. On top of that I was getting less and less sleep, averaging about four hours a night and waking up in a pool of sweat. So much so that I started keeping a towel next to me so I could wipe myself off. I wasn’t having nightmares, not that I could remember I was just completely physiologically coming undone, while mentally denying anything was wrong. I thought I was stronger than all of this and it wouldn’t break me. Yet the whole time I had a knot in the middle of me that just kept getting wound tighter and tighter.

Looking back I can see the warning signs. About Christmas time I started drinking more and more. I used to at least take the weekdays off but, I got to the point that I was drinking daily. On top of that I was getting less and less sleep, averaging about four hours a night and waking up in a pool of sweat. So much so that I started keeping a towel next to me so I could wipe myself off. I wasn’t having nightmares, not that I could remember I was just completely physiologically coming undone, while mentally denying anything was wrong. I thought I was stronger than all of this and it wouldn’t break me. Yet the whole time I had a knot in the middle of me that just kept getting wound tighter and tighter.

Then the break came. I had gone out drinking with a lot of friends, said some really inappropriate things to a girl I was into, got jealous when she wandered off and started flirting with another guy. I just buried those emotions down on top of the other ones.

This ended up being the catalyst for a full blown panic attack a few days later. So much so that I had to leave school, go back to my apartment and use my tried and true method of alcohol to calm my nerves. Only this time instead of taking the one shot I intended I ended up finishing the entire bottle.

Then I punched out a framed map of Afghanistan I had hanging on the wall, broke a few more things, then pulled out my gun. I don’t know how many times I put it to my head trying to end it all, but it was more than once. I also don’t remember messaging a friend of mine telling him I’m in a bad place. I do remember him and my roommate coming into the apartment seeing me drunk, crying, glass all over the place and the gun next to me. This wasn’t the first time I had come close to ending it all, but it was the first time alcohol took over and more importantly it was also the first time that I was scared of where I had gone and what I had almost done.

My friends cleaned the apartment up, cleaned me up and stayed with me all that night. My buddy took the gun away from me and I had no objections to that. After sobering up I realized I needed help, in a way I was never ready to acknowledge before. I thought I had my emotions locked up when I first came back from the army, I thought I was mentally strong enough to handle all the stresses I was facing and I never thought I would break like that.

My friends cleaned the apartment up, cleaned me up and stayed with me all that night. My buddy took the gun away from me and I had no objections to that. After sobering up I realized I needed help, in a way I was never ready to acknowledge before. I thought I had my emotions locked up when I first came back from the army, I thought I was mentally strong enough to handle all the stresses I was facing and I never thought I would break like that.

I’m extremely lucky I have made the connections I have, as I was able to call a nonprofit I used to work for, Operation Freedom Paws, and the angel of a woman who runs it, Mary Cortani, was able to get me an amazing therapist before anyone else could. It is absolutely heart-wrenching to write this down, to expose myself like this. It was so much worse to open up and tell my family all these things, as I thought I was protecting them by keeping it all inside. I do have to admit it has been the most healing thing I’ve ever done.

The feeling is like having the scar tissue ripped off of my heart, exposing those carefully crafted defenses I had built up in order to survive. What I’m coming to terms with is: I don’t have to live with those defenses anymore. I can trust my family and my friends with the darkness in my mind. It is OK to be vulnerable and that the only way to get past all the darkness is to bring it to the light.

The reason I’m choosing to do this is somewhere out there someone could be going through something similar and if this story has the chance to give them a way out from going the route I almost went, then I’m happy to pour it out.

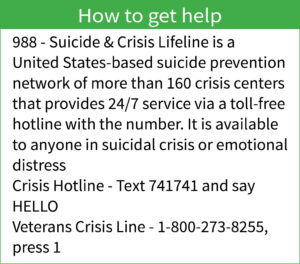

I am extremely fortunate that after opening up and telling people what I’m going through I’m getting asked “why didn’t I call” instead of standing over me asking “why didn’t he call.” So if you are out there and struggling to avoid hitting rock bottom and almost going the route I did, there are always people you can call and help you work through the darkness. All you have to do is be open to asking for help.

Connor Quinn is a veteran, having served nine years in the U.S. Army as a combat medic with two tours to Afghanistan. He holds a bachelor’s degree in health science from San Jose State University and is now pursuing a doctorate in chiropractic medicine at Palmer College of Chiropractic West. He is the co-author of the children’s book “Four Paws, Two Feet, One Team.”