Developers want to build a sand mining operation

![]()

By Marty Cheek

The future of more than 5,000 acres of prime rural property in southern Santa Clara County is in question as conservationists and a local Indigenous tribe seek to prevent the county from issuing a permit for a mining operation.

Photo courtesy www.protectjuristac.org

Amah Mutsun tribal members and supporters in 2019 marched to protest a mining operation on what they consider a sacred site.

Historically, the rolling hills several miles southwest of Gilroy off U.S. 101 have been known as Sargent Ranch, named after a family who owned it for several generations. The Amah Mutsun Tribal Band call it Juristac, meaning “place of the Big Head.” They consider the land a sacred site where their ancestors practiced healing ceremonies and dances for centuries. To the San Diego-based Debt Acquisition Company of America (DACA), the property’s owner, four hills on the site might serve as a potential open-pit sand and gravel quarry that will cover 350 to 400 acres.

The property encompasses two valleys, two creeks and several natural tar pits. The County Planning Department released a draft Environmental Impact Report (EIR) July 22 examining the impact of the mine. Their analysis found the project would cause “significant and unavoidable impacts” across at least six topics, including biological resources, cultural and tribal cultural resources, air quality, and transportation.

The property encompasses two valleys, two creeks and several natural tar pits. The County Planning Department released a draft Environmental Impact Report (EIR) July 22 examining the impact of the mine. Their analysis found the project would cause “significant and unavoidable impacts” across at least six topics, including biological resources, cultural and tribal cultural resources, air quality, and transportation.

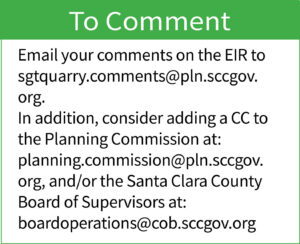

The public has until Sept. 26 to submit comments. After that date, the county planning commissioners and board supervisors are expected to consider the project and either approve or deny the permit for the mine. The Amah Mutsun and a coalition of allied organizations are planning a public rally at the county’s government headquarters in San Jose, with a tentative date of Sept. 12.

Juristac is the heart of Amah Mutsun spirituality and culture, said Valentin Lopez, chairman of the tribal band. For thousands of years, the ancestors made their home and held sacred ceremonies in the hills. Most of these ceremonies came to an end when the people were forcibly removed to Mission San Juan Bautista by Spanish missionaries in the late 1700s.

After Mexico ended the mission system in 1833, many of the surviving Amah Mutsun returned to Juristac to live in their traditional ways in harmony with nature, Lopez said. In 1862, a smallpox epidemic wiped out 90 percent of the tribe and the remaining 10 percent were removed.

A padlocked gate now stands between the tribal members and their ancestral lands. The proposed mining project insults the tribe’s cultural and spiritual traditions, Lopez said.

“When we heard of the sand and gravel pit, we knew how destructive that would be to our most sacred site, to our most cultural site. And our tribal council immediately wrote a resolution (to the county) opposing the Juristac (mine),” he said. “This project represents a continuation of the destruction and domination our Amah Mutsun people have suffered for generations. The cultural survival of our tribe is at stake.”

DACA managing member Howard Justus believes the quarry will supply a more environmentally sustainable source of sand used for concrete used in Bay Area construction. Today, most of this material is shipped by barges from a quarry in Vancouver, he said.

“The sand that Sargent Ranch will supply is going to come with a carbon footprint that is 25 percent of the carbon footprint to bring sand in from British Columbia,” he said.

“The sand that Sargent Ranch will supply is going to come with a carbon footprint that is 25 percent of the carbon footprint to bring sand in from British Columbia,” he said.

If the county does not approve the permit, the owners will consider building homes on the property, which now has seven parcels approved but can hold up to 20 parcels, Justus said. A few years ago, the company sold about 1,500 acres of its original purchase that was in Santa Cruz County. This property is called Pescadero Ranch.

“The tribe would in no way benefit from it if (home development) is the route we go,” Justus said. “And that would probably have a very negative impact on conservation.”

If the quarry is allowed, the rest of the land would be put into a combination of conservation and beneficial uses for the Amah Mutsun, he said.

“We believe all three uses — the quarry, the tribal uses, and conservation — can co-exist quite harmoniously on the ranch,” Justus said.

According to the draft EIR, the mine would impact more than 400 acres of grassland and oak woodland habitats, irreversibly altering the landscape at Juristac. The mine operators would dig giant, open pits into the hillsides and build a processing plant the size of 14 football fields. Aggregate processing would require more than 80,000 gallons of water a day to be pumped from the ground. The erosion and runoff from the mining operations, roads, and waste piles could contaminate both Sargent and Tar Creeks, which flow to the Pajaro River, an already heavily impaired watershed.

As part of the environmental review process, the county planning commission also authorized an ethnographic study. The resulting confidential 285-page report provides a detailed review of archaeological, ethnographic and oral historical records, unequivocally documenting the historical, cultural and religious importance of Juristac to the Amah Mutsun.

As part of the environmental review process, the county planning commission also authorized an ethnographic study. The resulting confidential 285-page report provides a detailed review of archaeological, ethnographic and oral historical records, unequivocally documenting the historical, cultural and religious importance of Juristac to the Amah Mutsun.

Environmental protection is another factor in consideration regarding the mine. Potentially endangered species such as mountain lions and California red-legged frogs need room to roam through the property to prevent genetic isolation and local extinctions, especially as the climate crisis intensifies, said Tiffany Yap, senior scientist and wildlife connectivity advocate at the Center for Biological Diversity, in a press release from Green Foothills. The nonprofit based in Palo Alto advocates for open space.

“The proposed mine will forever destroy lands within one of the most critical wildlife linkages between the Santa Cruz, Diablo and Gabilan mountain ranges,” she said. “This entire property is a top conservation priority because it’s a biodiversity hotspot where wildlife can move between mountain ranges.”

Green Foothills has opposed Sargent Ranch development proposals since 1993, said Alice Kaufman, policy and advocacy director with the nonprofit. These included a plan to build four “villages” of more than 12,000 residents, a proposal for two golf courses, and a luxury residential development. Nearly a decade ago, the property owner declared bankruptcy, and the land was acquired by creditors, including DACA.

Green Foothills has opposed Sargent Ranch development proposals since 1993, said Alice Kaufman, policy and advocacy director with the nonprofit. These included a plan to build four “villages” of more than 12,000 residents, a proposal for two golf courses, and a luxury residential development. Nearly a decade ago, the property owner declared bankruptcy, and the land was acquired by creditors, including DACA.

“In the year 2022, why are we still considering destroying critical wildlife habitat and sacred Indigenous land for an open-pit sand mine that nobody is asking for?” she said in a press release. “Local folks and environmental groups defeated development efforts at Juristac twice in the last two decades. It’s time to rally again and protect these sacred, environmentally critical lands.”