The pursuit of inner peace is what brings many visitors to Coe today

![]()

Hikers traverse a trail near Rooster Comb in Henry W. Coe State Park’s Orestimba Wilderness. The park is a hidden gem in Santa Clara County.

Photo courtesy Ron Erskine

By Calvin Nuttall

Calvin Nuttall

Luckily for us South Valley residents, the second largest state park in California is right in our backyard. For myself and many other locals, experiencing nature and reconnecting with the land are vital parts of maintaining our health and happiness. Henry W. Coe State Park provides a marvelous wilderness destination for us to do this.

Luckily for us South Valley residents, the second largest state park in California is right in our backyard. For myself and many other locals, experiencing nature and reconnecting with the land are vital parts of maintaining our health and happiness. Henry W. Coe State Park provides a marvelous wilderness destination for us to do this.

The park’s dedicated volunteers maintain stewardship over more than 87,000 acres of former ranchland and wilderness. Many visitors come to Coe for recreational activities such as hiking, trail running, mountain biking, and horseback riding. Its vast terrain offers something for folks of any experience level, from the first-time wanderer to the hard-core explorer. As regulars to the park say, “You hike in the Sierras to train for Coe’s backcountry.”

The park is largely maintained and overseen by its volunteers, a well-coordinated network of passionate locals who devote time and energy to ensuring that Coe remains accessible to the public. These volunteers are trained by the Pine Ridge Association, a nonprofit group dedicated to maintaining Coe for visitors. They are an excellent source of knowledge about the park’s past and present.

Veteran and newcomer volunteers alike can learn about the park and its history, geology, flora and fauna at the organization’s annual Coe-Ed Day event. This year it took place Oct. 29 at the park’s headquarters and I was invited to attend the workshops and keynote speech.

Coe-Ed Day featured presentations from both veteran park rangers and academics researching the park’s unique features. Park rangers led groups of volunteers on a walking tour through the forest near the headquarters, highlighting the region’s mighty oaks and pines.

San Jose State University geology professor Dr. Ellen Metzger and several of her students presented their research into the park’s geologic history.

They delved into the land’s mineral composition and how the terrain formed. Graduate students from Cal Poly and SJSU gave lectures on the mosses, lichens and ferns that populate the streams and gullies of Coe. Volunteers listened to immersive soundscapes recorded in various locations in the park and learned how to identify birds by their calls.

They delved into the land’s mineral composition and how the terrain formed. Graduate students from Cal Poly and SJSU gave lectures on the mosses, lichens and ferns that populate the streams and gullies of Coe. Volunteers listened to immersive soundscapes recorded in various locations in the park and learned how to identify birds by their calls.

When you appreciate the complexity of Coe’s landscape and how every element of its ecosystem interacts and coexists, your experience as a visitor becomes richer.

Rocks are not merely rocks, they are outcroppings of serpentinite deposited here by the motion of an ancient tectonic plate boundary that has not existed for millions of years, but the marks of that movement can be seen in the landscape all around you as you follow the park’s trails. The gnarled, twisted tree you might have walked past without a second thought could be a live oak older than the United States.

The grassy hillside may conceal a venerable bobcat, watching you warily as you wander through its domain.

Seventy years ago, Sada Coe Robinson gave Santa Clara County 12,230 acres of her family’s former cattle ranch to preserve it for public use as a park dedicated in the name of her father, Henry W. Coe. The land was a county park until 1958 when it was sold to the state of California for $10, after which it became a state park.

Seventy years ago, Sada Coe Robinson gave Santa Clara County 12,230 acres of her family’s former cattle ranch to preserve it for public use as a park dedicated in the name of her father, Henry W. Coe. The land was a county park until 1958 when it was sold to the state of California for $10, after which it became a state park.

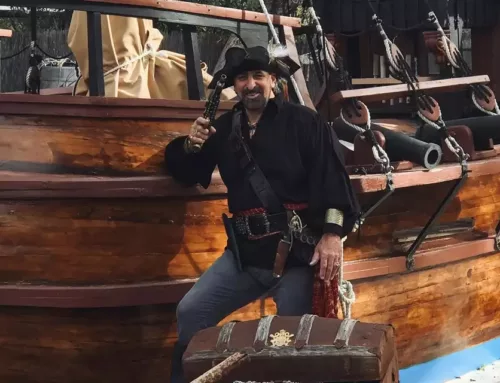

Not far from the park headquarters, a small stone monument dedicated to Henry Coe bears the inscription: “May these quiet hills bring peace to the souls of those who are seeking.” This pursuit of inner peace is what brings many visitors to Coe today, where they can escape from the hectic urban environment of the Bay Area and its demands and pressures.

Calvin Nuttall is a Morgan Hill native with a passion for nature, science, and technology. This is the first of a series of his columns encouraging people to discover Henry W. Coe State Park.