‘Atmospheric rivers’ fill state reservoirs, reducing impact of years of drought

![]()

Curious people check out the major flooding at Miller’s Crossing in Gilroy’s Christmas Hill Park. Torrential rains have battered the South Valley region since late December. Photo by Marty Cheek

By Marty Cheek and Robert Airoldi

Morgan Hill residents faced the aftermath of a relentless series of torrential storms that pounded California for three weeks starting in late December, causing widespread damage to homes, businesses and infrastructure.

Since Christmas Eve, nine storms battered California. Clean-up from the “bomb cyclone” storms could exceed $1 billion, according to the state’s emergency agency.

Since Christmas Eve, nine storms battered California. Clean-up from the “bomb cyclone” storms could exceed $1 billion, according to the state’s emergency agency.

Twenty people died from storm-related fatalities. That’s more than the number who lost their lives in the state’s wildfires for the past two years.

Morgan Hill received 18.05 inches of rain from Dec. 26 through Jan. 19, according to Chris Henry, with the Morgan Hill Rainfall Facebook group. Our annual average is about 25 inches. This is more than half the annual average.

“As far as getting rain the past three weeks, that’s not been abnormal, but it’s so many back to back to back that is the unusual part, for sure,” said Sarah McCorkle, meteorologist with the National Weather Service in Monterey.

An estimated 24.5 trillion gallons of water fell on California during the series of storms, filling reservoirs. This is more rain that has fallen on the state since Abraham Lincoln was the president and the state faced 43 days of rain in the winter of 1861/62. The storms added more than five million acre-feet of water to California’s supply. That’s the yearly use of 24 million people.

In the Sierra Nevada mountain range, the snowpack reached a two-decade record of more than 227 percent of normal, helping to put what climate scientists consider a serious dent in the drought with the spring melt.

Highway 101 Jan. 9 during the flooding that closed the road. Photo courtesy California Highway Patrol.

“We are no longer in an ‘extreme’ drought but still in a ‘moderate’ drought,” McCorkle said. “We still have a ways to go but the recent storms have definitely improved the situation.”

The gauntlet of powerful “atmospheric river” storms — corridors of highly concentrated water vapor moving quickly in streams high above the Pacific Ocean — turned South Valley streets into rivers and farm fields into lakes. Downed trees, road closures and power outages impacted sections of South Valley, leaving residents to pick up the pieces and make repairs as they struggle to recover from the severe weather.

The California Highway Patrol closed U.S. 101 south of Gilroy for six hours Jan. 9 after overflow from Uvas Reservoir spilled over the dam into Uvas Creek near Mesa Road. Downstream, muddy knee-deep water stranded several cars. The massive traffic jam that afternoon sent vehicles into side streets in Morgan Hill and Gilroy.

One Hollister resident said he left San Martin at 3 p.m. that day and got home three hours later.

Workers clear vegetation from a creek. Photos by Marty Cheek

Video from the KPIX CBS News helicopter showed several homes near the 101/25 overpass, including the historic Calhoun Ranch home, submerged to the first floor level. Only the roofs could be seen of several parked vehicles outside the houses.

The usually dry Uvas Creek turned into a raging river flowing through Christmas Hill Park Tuesday, Jan. 10, attracting a number of residents who gathered along the edges and took photos and videos of the rapid torrent.

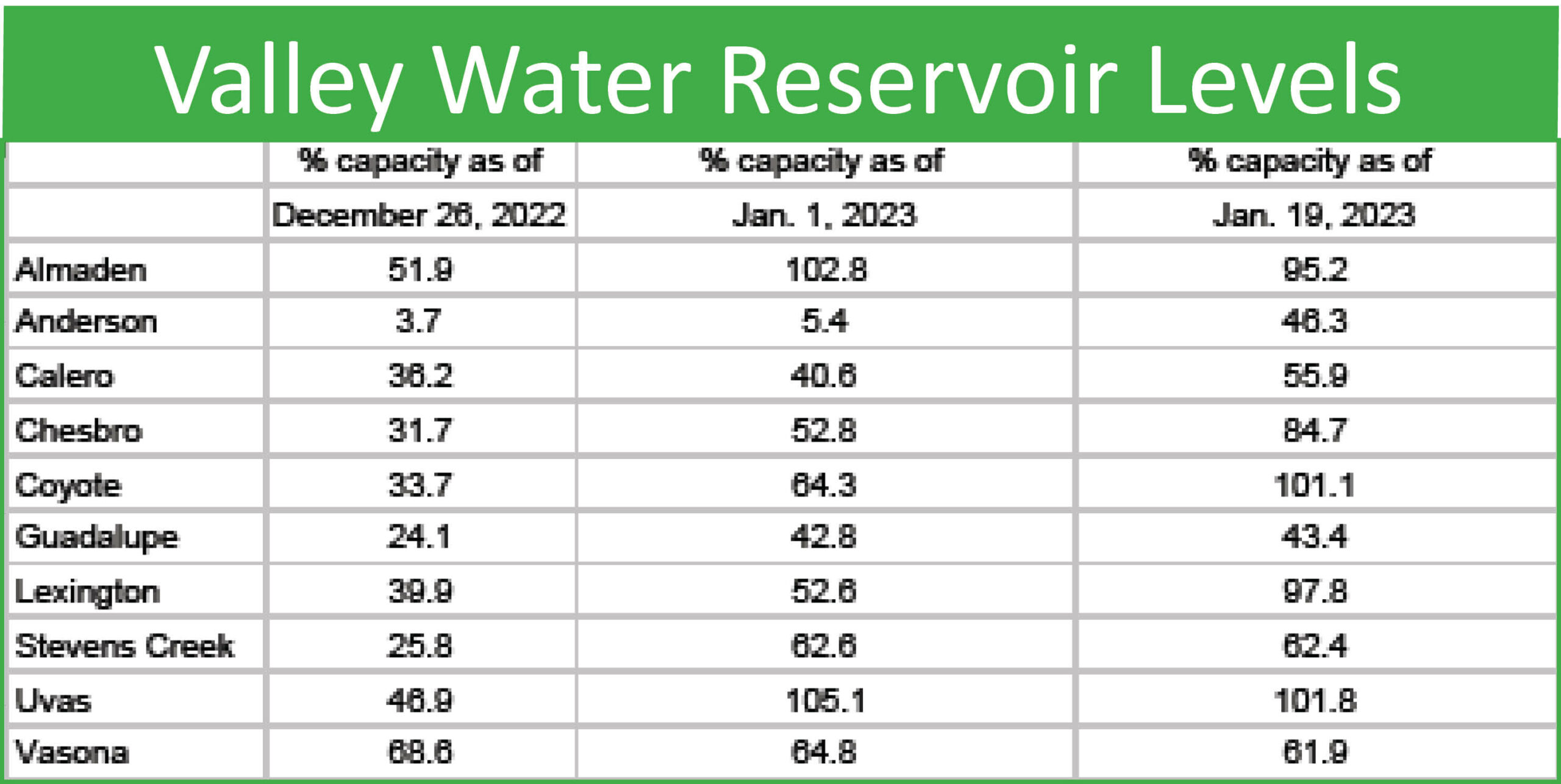

Valley Water closely monitored the flooding of county creeks and the amount of water filling the 10 reservoirs it manages. They worked with cities and local jurisdictions on flood watches to prepare people for possible evacuations. Valley Water distributed more than 100,000 sandbags in the county during the storms, including sites in Gilroy and Morgan Hill.

Anderson Reservoir, now undergoing a $1.2 billion earthquake retrofit project, is required by the federal government to be at 3 percent of capacity. With the storms, it went to 46.3 percent of capacity. Water is being drained through an outlet pipe into Coyote Creek, said Matt Keller, media supervisor for Valley Water.

“

This has been unprecedented to get this much rain in such a short amount of time — to get those atmospheric rivers back to back to back,” he said. “It has been impactful to all the people in Santa Clara County and all the people in the Bay Area and California as well.”

During the summer and fall, Valley Water conducts a stream maintenance program to clean out waterways of debris and other blockages. During winter storms when creeks are high, the job can become dangerous if giant trees fall into the waterways when roots are loosened in the sediment. They must be removed to prevent potential flooding.

“That’s really a big part of the work we do is to make sure those creeks are not seeing any blockages from debris that goes in,” Keller said. “Mother Nature delivered quite a few storms and a lot of water into the watershed.”

More than 4.5 million Californians faced flood watch warnings, and thousands were displaced throughout the state. A spokesman for the California Governor’s Office of Emergency Services called the seemingly nonstop deluge “one of the deadliest disasters in the history of our state.”

Photo courtesy KPIX CBS News

The deaths include Kyle Doan, a 5-year-old boy in San Miguel in San Luis Obispo County. A powerful current swept him away from his mother’s arms after their truck got trapped in a flooded creek on the way to his school Jan. 9. No lives were reported lost in the South Valley.

President Joe Biden issued an emergency declaration Jan. 9 to support storm response and relief efforts in more than a dozen California counties. Jan. 19, he visited Aptos and Capitola to survey some of the storm damage.

Valley Water activated its Emergency Operations Center Dec. 31 due to heavy rainfall and flooding and provided relief operations throughout the county. Flooding occurred along San Francisquito Creek, Upper Penitencia Creek, West Little Llagas Creek and Uvas Creek.

Click HERE to read sidebar story on comments from Morgan Hill Police Chief Shane Palsgrove

Climate scientists call California’s recent storm pattern a “precipitation whiplash.” On a historic perspective, rains in recent decades are heavier and more catastrophic at the same time droughts can last longer and be more intense. Global warming contributes to the overall heating of the atmosphere to create a higher level of weather variability.