As a child, Hubert Yoshida spent years in the Poston relocation camp

![]()

By Calvin Nuttall

Hubert Yoshida knew danger lay potentially everywhere as he led his rifle platoon through a dense Vietnamese jungle in March 1965. Their mission: rescue a company of fellow Marines trapped by the North Vietnamese Army.

Hubert Yoshida knew danger lay potentially everywhere as he led his rifle platoon through a dense Vietnamese jungle in March 1965. Their mission: rescue a company of fellow Marines trapped by the North Vietnamese Army.

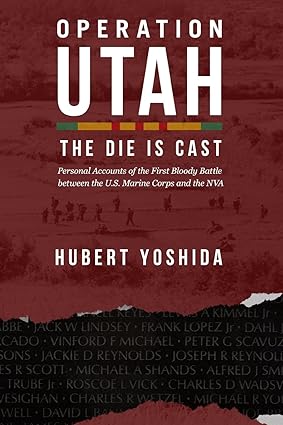

Operation Utah was the first battle of the Vietnam War between the United States Marine Corps and the NVA, and Yoshida found himself in the thick of it.

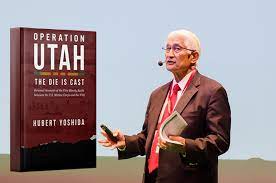

“It was one of the fiercest battles of the war,” Yoshida said, speaking at a book signing for his memoir Operation Utah: The Die is Cast at the Morgan Hill Community Center Nov. 8. “I was a rifle platoon commander at that time, in H Company. Our mission was to rescue the 1st Platoon of F Company that had been cut off by the North Vietnamese.”

Born in Salinas in 1939, he grew up in Watsonville where his parents farmed. During World War II, he and his family were Americans of Japanese heritage held by the federal government in the Poston relocation camp in Colorado.

Yoshida idolized the Japanese Americans fighting in the U.S. Army 442nd Infantry Regiment in Europe, which included his uncle and cousin.

He joined the Marine Corps in 1965 straight out of college after studying mathematics at the University of California, Berkeley. In Vietnam, he received two bronze stars for valor. His memoir serves as a tribute to the troops killed during Operation Utah. The families of those fallen service members inspired the book because they were “hungry for answers” as to what had happened to their loved ones, Yoshida said.

Yoshida’s quest began in 2016 when he revisited the site where Operation Utah took place. He met General Thieu of the NVA. Together, with an interpreter, they walked the battlefield and reflected on the war.

“He invited me to his home for tea,” Yoshida said. “It is kind of strange, being in the home of somebody who had killed so many of us, and we had killed so many of them. I had been in Vietnam for 12 months fighting my war, but he was there for 30 years, fighting the French, the Americans, the Chinese.”

In Thieu’s home, Yoshida saw an altar on which incense burned before a photo of wartime Vietnamese president Ho Chi Minh, and another of General Giáp, who commanded the NVA.

“Now, I doubt any American veteran has a picture of President Johnson or General Westmoreland in their living room,” Yoshida said. “This is how dedicated and committed he was to their way of life and to their government. I have nothing but respect for the enemy we had at that time.”

Following his visit, Yoshida penned a blog. It gained traction with the families of fallen soldiers. Many reached out to him with the same or similar questions.

“What they wanted to know was, how did their loved ones die?” Yoshida explained. “Because when somebody was killed, they got a short telegram from the government. What does that mean to somebody who has just lost a loved one? They want to have more information than that, and it is rare they get it.”

Yoshida began to contact other veterans who were a part of Operation Utah. He scoured the Internet to find more people who could describe how these men had been killed. As he collected these stories, he decided to write a book.

“I wished I had started sooner,” he said. “So many of them had already passed away. In fact, since I wrote the book, in the past two years about five of the men I interviewed have died.”

The process also served as closure for Yoshida. In answering these questions for others, he answered many of his own lingering questions about the war and the fates of the men he had gone into battle with.

“As a veteran who was engaged in combat, I only saw what was around me,” Yoshida said. “I didn’t know what was happening with the other battalions, or the helicopters or the artillery.”

The Vietnam Memorial Wall in Washington, D.C. lists names of the Americans who died by date of their deaths. The names of the 102 men killed in Operation Utah can be found on Panel 5 East. In total, 21 men from South Valley gave their lives during the war.

The name of one American soldier who fought in Vietnam, however, was missing from the wall. Private First Class John Nishimura came from a large farm family in Morgan Hill who still live here. Paralyzed from the neck down by a shot that severed his spinal cord, the military sent Nishimura first to San Francisco and then to Long Beach. He died in the hospital four months after he was wounded.

“When his family went to Washington, D.C., to see his name on the Wall, it was not there,” Yoshida said. “They said it was because John had not died in a combat zone, he had died in Long Beach, so he supposedly did not belong on the wall. Susie Nishimura didn’t believe that was correct, so she started a campaign on her own, writing generals and congressmen and everybody she could to get that changed.”

Because of Nishimura’s efforts, when the traveling version of the wall arrived in Sacramento, her family received a special invitation to appear as guests of honor. When unveiled, not only was John Nishimura’s name there, but the names of 10 other men who met similar fates.

Yoshida believes many Americans who served in Vietnam deserve to be honored on the wall.

“I gave this talk once before, and afterward a man came to me and said he had a relative who had committed suicide after he came back from Vietnam,” he said. “That is a new population who should be on that wall. They didn’t suffer a physical wound, but they had a mental wound, a spiritual wound that caused them to commit suicide.”

Calvin Nuttall is a Morgan Hill-based freelance reporter.