One-time winemaker leads local history buffs down memory lane

![]()

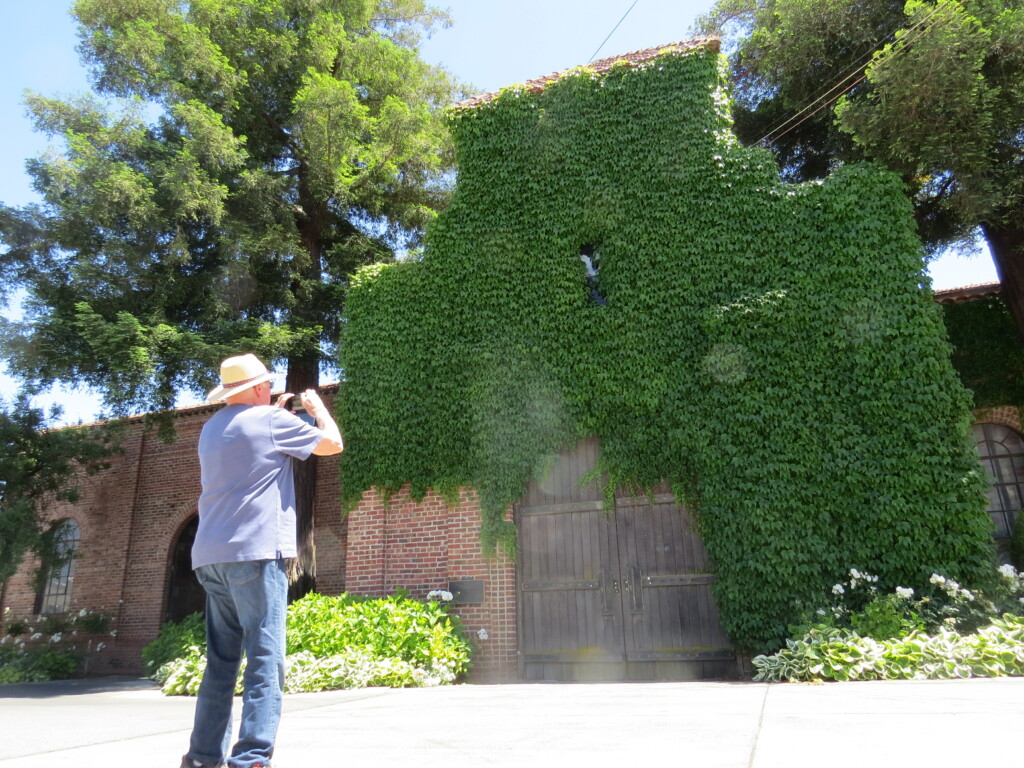

Photo by Calvin Nuttall

Phill Laursen, a Gilroy Historical Society member, takes a photo of the former San Martin Winery building. The Filice family sold the business in the 1970s and it is now operated by ASV Wines.

By Calvin Nuttall

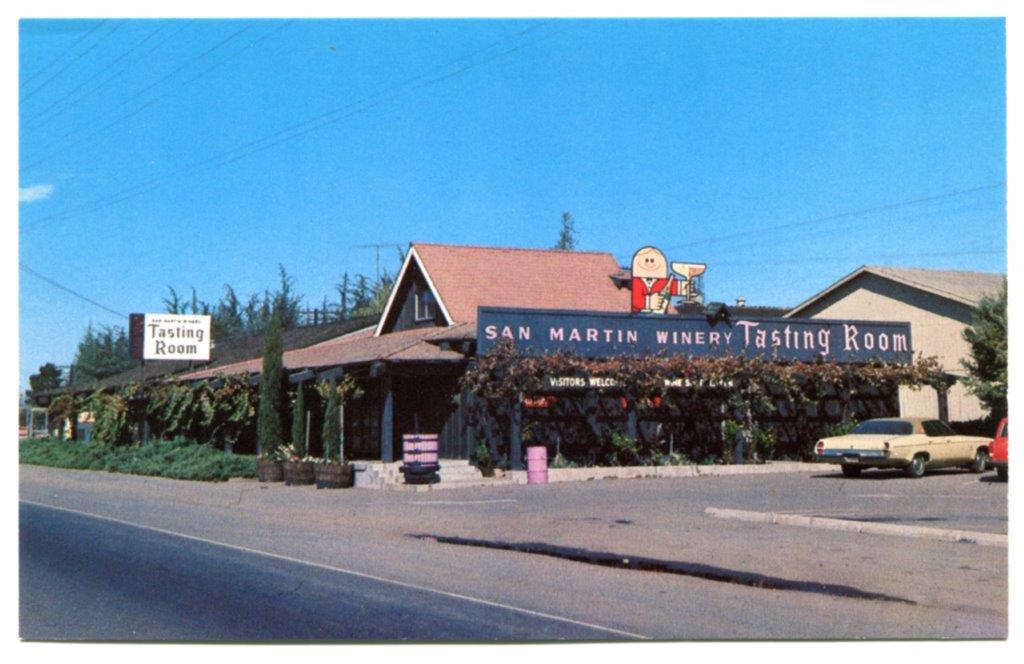

The old San Martin Winery tasting room next to the site. Photo courtesy Mission View Wines blog

Half a century ago when Santa Clara Valley was renown as a hub of California winemaking, the San Martin Winery stood at its heart. For Tim Filice, it served as his second home.

The historic Bruno Filice Building remains hidden away by the railroad tracks at the corner of South and Depot streets in San Martin. Located at the end of an entrance avenue guarded on both sides by a sentry of towering trees, the brick-and-mortar winery stands proudly with nearly a century of tales to tell. Arched doorways and windows and a terra cotta tile roof impress visitors.

The grand-sized wooden doors provide a warm welcome. A second-story tower with a steep roof guards the main entry. Ivy covers portions of the building constructed in the 1930s by Bruno Filice, Tim’s grandfather. Three generations of winemakers practiced their craft there until the family sold the property in the 1970s. Today, it is owned by ASV Wines.

Tim Filice led an afternoon tour of the historic winery building June 4 for a small group organized by Karen Pedigo of the Gilroy Historical Society with the help of Andrew Beckwith, the ASV plant manager. In the dark, cool storage building, surrounded by pallets loaded high with various brands of wine, Filice shared with the history buffs his memories of the family wine business.

Photo by Calvin Nuttall

“I have really not been back here for a lot of years,” he said, recalling his younger days here. “I have a lot of happy memories here. I basically grew up here, I didn’t live here but I was here weekly. After a time as an apprentice on one of the ranches down in Gilroy, I came here — and it was like graduating.”

Bruno Filice arrived in San Jose by way of the Northern Pacific Railroad after immigrating to the United States from Italy. He set up shop with a grocery store in the Lincoln Avenue area of San Jose then known as Goosetown, an Italian-American immigrant neighborhood.

“My grandfather had eight kids,” Filice said. “In order to help feed all of those eight kids, he went directly to farmers to buy whatever they needed. Eggs, vegetables and so forth. As the story goes, the neighbors who were aware of this would ask him, ‘Hey Bruno, when you go to the egg farm get a flat for me,’ and so forth. That kind of grew into our grocery store, on South First Street.”

When the Prohibition era began in 1920, most winemakers went out of business. Those that survived converted their operations to the production of altar wine, or other fermented products. Among the businesses that went under was the facility that formerly operated at the site of what would later become the San Martin Winery.

“When my family became aware of this facility, it was just after the repeal of Prohibition,” Filice said. “They were interested in getting into the wine business. In those days, Santa Clara County was the epicenter of winemaking here in this part of California.”

During World War II, the winery was not doing well, Filice said. Fortunately, they were approached by the U.S. government with a contract: to distill wine into alcohol, for use in the war effort.

“I don’t think the family was ever told exactly what the alcohol was used for,” he said. “But the family myth was that it was used to power torpedoes. The story goes that the winery didn’t make a lot of wine during the war, but they certainly made a lot of torpedo fuel.”

The contract allowed the business to remain a source of stability for the group during a difficult financial period.

“We had a big group of families to support, five or six families depending on who was in and who was out, a lot of mouths to feed,” Filice said. “We used to call this place ‘the trough.’ Everybody could come and feed. A lot of the kids were employed here. I spent countless summers on the bottling line and elsewhere.”

As their business grew, the Filices realized they needed to do more than make wine. They needed to grow their own grapes as well. Vineyards in those days grew what were called “field blends,” which included various types of grapes that were grown together and sourced from family vineyards dotting all over Northern California.

As their business grew, the Filices realized they needed to do more than make wine. They needed to grow their own grapes as well. Vineyards in those days grew what were called “field blends,” which included various types of grapes that were grown together and sourced from family vineyards dotting all over Northern California.

“The wines that were made from some of those grapes in those early years were of questionable quality,” Filice said. “The family decided that they wanted to have a more consistent supply of quality grapes and decided to begin to acquire land, so that they could plant their own vineyards and ensure a supply of good fruit.”

Soon after, the family decided to diversify. They began purchasing orchards to keep their vineyards company, he said.

“As a single-crop grower, a lot of your equipment stands idle for much of the year,” he said. “So we decided to diversify into stone fruit. We acquired an apricot and cherry orchard in Morgan Hill, and various other little properties here and there in order to grow cherries.”

During its heyday, the San Martin Winery was best known for its tasting rooms. They were some of the first such businesses in the region.

The side business proved to be quite lucrative, and helped the family business to survive through a difficult period in the wine industry’s history in the 1950s.

“The wine business again hit an oversupply time during the ‘50s, and it became very difficult to make a buck in the business,” Filice said. “The tasting room business is lucrative, because there is no middleman. Basically, you take the wine out here, run it across the tracks, and there was nobody in between. It was a good business. At our peak I think we had seven or eight tasting rooms in various areas of California.”

The family eventually decided to sell the winery in the 1970s, as the industry was undergoing huge fundamental changes, becoming more corporate and standardized.

“We had a big decision to make, and that was to take on debt and get big, or to sell the place,” Filice said. “Our family has been very risk-averse over the years, and so we elected to sell it. We sold it to a big conglomerate out of Texas, and it has changed hands quite a few times. I am happy to see that it is still being used in the use for which it was intended.”

Calvin Nuttall is a Morgan Hill-based freelance reporter and columnist.