Anaerobe Energy is using bacteria to process agriculture “waste”

![]()

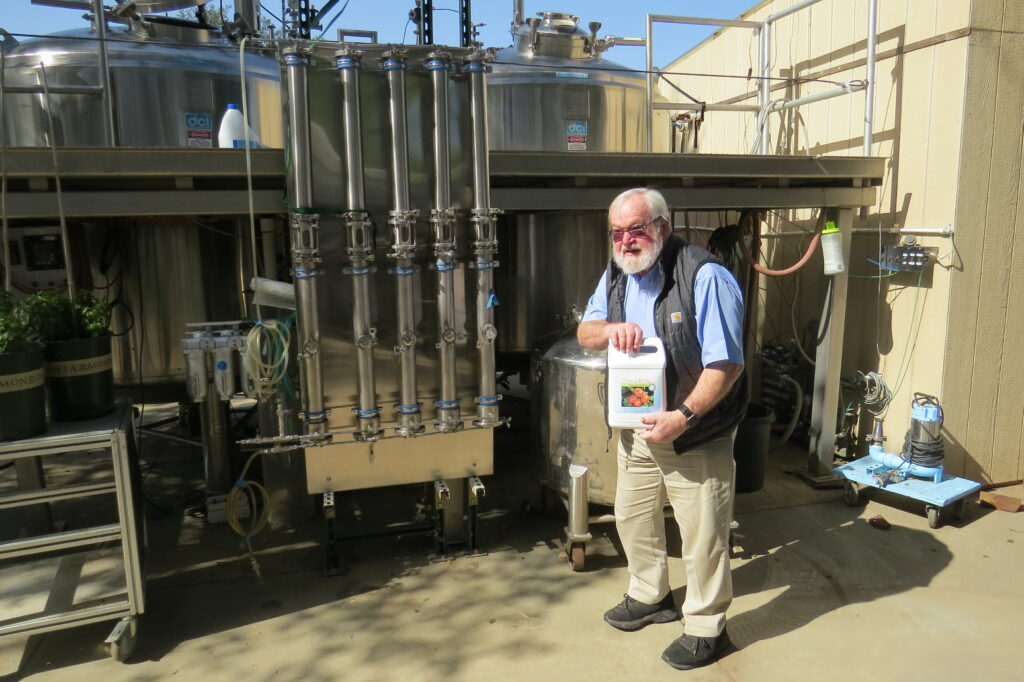

Photo by Calvin Nuttall

Miguel Lopez, Anaerobe energy manager, holds a handful of grape pomace, soon to be hydrogen and FermeGrow fertilizer.

By Calvin Nuttall

When Mike Cox began experimenting with his “continuous anaerobic fermentation system,” he was seeking to find the fuel of the future. In his search, he instead stumbled across an unexpected byproduct that may soon revolutionize modern agriculture.

The project that would eventually spawn Anaerobe Energy, the Morgan Hill-based microbiologist’s latest business venture, began with the pursuit of a system that could economically produce the gaseous element hydrogen from agricultural waste.

This gas would be used as a source of energy to power the system in a carbon-negative loop, with extra hydrogen left over as an energy product.

Photo by Calvin Nuttall

“It always worked, but it took 10 times as much energy to heat-sterilize the biomass as the hydrogen energy I got back,” he said. “Financially, it was upside-down. But I hadn’t given up, because there are times and places where hydrogen, even at that cost, could still be an advantage, because it is needed for a particular reason.”

One day, during these initial experiments, Cox received a visit from Ian Teresi, farm manager at George Chiala Farms. Cox was cleaning out one of his fermentation tanks, getting rid of the liquid byproduct.

“Ian saw this brown stuff in there and said, ‘Give me a bottle, I want to get a sample of that,’” Cox said. “He sent it off, and when he came back, he said, ‘Mike, I’m paying $5 a gallon for that stuff you’re throwing away.’ He said it’s a great fertilizer.”

Since making this discovery, further research has revealed why this byproduct makes such an excellent fertilizer — it’s all about the microbes.

Rather than directly feeding nutrients to the plants, as a traditional fertilizer does, the liquid contains everything needed to help soil microbes thrive, and it comes pre-inoculated with two strains of spore-forming bacteria, Clostridium acetobutylicum and Clostridium pasteurianum.

“This way, we feed anything with roots,” said Kristie Ashley, Anaerobe Energy’s sales manager. “Through a symbiotic relationship, the microbes communicate directly with the roots via ‘quorum sensing,’ and they can provide the ideal quantities of nutrients that each individual plant requires, and the plants are then able to produce the nutrients the microbes need in exchange.”

Photo by Calvin Nuttall

Quorum sensing is a mechanism by which microbes such as these Clostridium strains can communicate by exchanging chemical signals. This lets them know exactly what nutrients their host plant needs.

“These incredible anaerobes solubilize the potassium and phosphorus and fix the nitrogen present in the soil, making these available to the plants,” Ashley said. “The microbes create the nutrients or fertilizers required, in perfect amounts, for each plant that they interact with. Never too much, never too little, just what the plant is asking for.”

It is thanks to this reciprocal process, she said, that their fertilizer does not deplete the soil with repeated use. And because it does not contain large amounts of nitrogen, potassium, or phosphorus (chemicals present in traditional fertilizer), it does not generate harmful runoff of excess nutrients, which can cause environmental damage through toxic algae blooms and deoxygenated “dead zones.”

“Traditional composting takes about 45 to 90 days to complete a cycle, it consumes a considerable amount of water, potentially creates air and water contamination, and releases significant CO2 in the process,” Ashley said. “Our patented system takes two days to complete a cycle, and emits zero CO2 into the atmosphere.”

This speedy process allows them to quickly transform plant waste materials brought in by local growers into productive fertilizer, which they can then sell back to the very same growers.

“Our raw materials are also locally sourced, rather than shipped across the country or across oceans,” Ashley said. “Many of the synthetic fertilizers available on the market require massive transportation costs. Our current sources of nitrogen actually come from Russia and the Middle East, potassium from Canada, phosphorus from Florida and Morocco, so Morgan Hill and Gilroy are a much shorter journey than the industry options.”

“Our raw materials are also locally sourced, rather than shipped across the country or across oceans,” Ashley said. “Many of the synthetic fertilizers available on the market require massive transportation costs. Our current sources of nitrogen actually come from Russia and the Middle East, potassium from Canada, phosphorus from Florida and Morocco, so Morgan Hill and Gilroy are a much shorter journey than the industry options.”

The company’s patented fermentation process produces two types of byproducts: solid and liquid. The liquid is marketed as a fertilizer under the name FermiGrow, and the solid byproducts are mixed with biochar and sold as a soil amendment called FermiChar.

“One drawback of mixing raw biochar into your soil is that it will initially take up the nutrients, moisture and microbes, reducing the potential for plant growth,” Ashley said. “What we’ve done is eliminate that initial equalization phase. By preloading the amendment with the anaerobes and everything they need to proliferate, Fermichar starts working immediately to bring soil to its optimal balance state without fear of potentially shocking your plants.”

Despite his unexpected success as a fertilizer manufacturer, Cox isn’t ready to give up his pursuit of hydrogen just yet. He envisions a system capable of capturing the hydrogen released during the fermentation process, with the goal of building a system that is self-sufficient, creates its own fuel, and potentially powers other equipment.

“The goal is to design a system that transforms the way we address agricultural biowaste as well as fertilization practices,” Ashley said. “This is 100 percent circular agriculture.”

In the future, Cox plans to expand his research to include a wider variety of soil bacteria, and perhaps even offer custom blends of “designer” bacterial cultures for specific applications. Some bacteria help to better protect against nematodes, for example; others produce special nutrients, or help with soil aeration.

“At the moment, we have one bottle with bacteria in it,” he said. “In a couple of years, I want to have 150 bottles with different bacteria. This is a field that is pretty much an open frontier, and we probably are ideally suited to do this because we are in the middle of an agricultural area and we know the microbiology.”

Calvin Nuttall is a Morgan Hill-based freelance reporter and columnist.