Dr. Marshall’s system trains people in county jails with job skills

![]()

Photo courtesy NCORE

Dr. Patrick Marshall won the Change Agent of the Year award at the National Congress of Race and Ethnicity in Hawaii

By Daniel Edwards

From behind bars, Alex discovered potential career paths. He never imagined his time incarcerated at Elmwood Correctional Facility would lead him from simply wanting to be a better pet owner to dreaming of a future in animal handling.

From behind bars, Alex discovered potential career paths. He never imagined his time incarcerated at Elmwood Correctional Facility would lead him from simply wanting to be a better pet owner to dreaming of a future in animal handling.

Thanks to Dr. Patrick Marshall’s innovative education program in Santa Clara County jails, inmates like Alex are finding new purpose and unexpected opportunities. A strong advocate for education of all people, his work especially includes training incarcerated individuals for a better life after they re-enter society.

“We want to give people a fundamental right to access education,” he said. “That’s what drives me.”

Marshall designed his system to give inmates a college-level education with instructors coming into the jails to teach them. This enables them to pick a career path of their choosing.

“Where most people are going in there (the jails) — especially in justice systems — they barely get education. They barely get rehabilitation,” he said. “Now they have a plethora of opportunities to have success.”

Thanks to Marshall’s system, inmates who go through college courses in jail can enter local community colleges when they are released, allowing them to continue their education.

He introduced his College Collaborative System in county jails in 2018. For his success in training incarcerated men and women over the years, colleges and officials acknowledged his efforts in May. Marshall earned the Change Agent of the Year award in Hawaii at the National Congress of Race and Ethnicity (NCORE) conference.

He expressed his surprise at the magnitude of the award, standing in front of an audience of thousands, who were all ready to hear his presentation. Marshall told them about how the impact of his work was the most important part for him.

He expressed his surprise at the magnitude of the award, standing in front of an audience of thousands, who were all ready to hear his presentation. Marshall told them about how the impact of his work was the most important part for him.

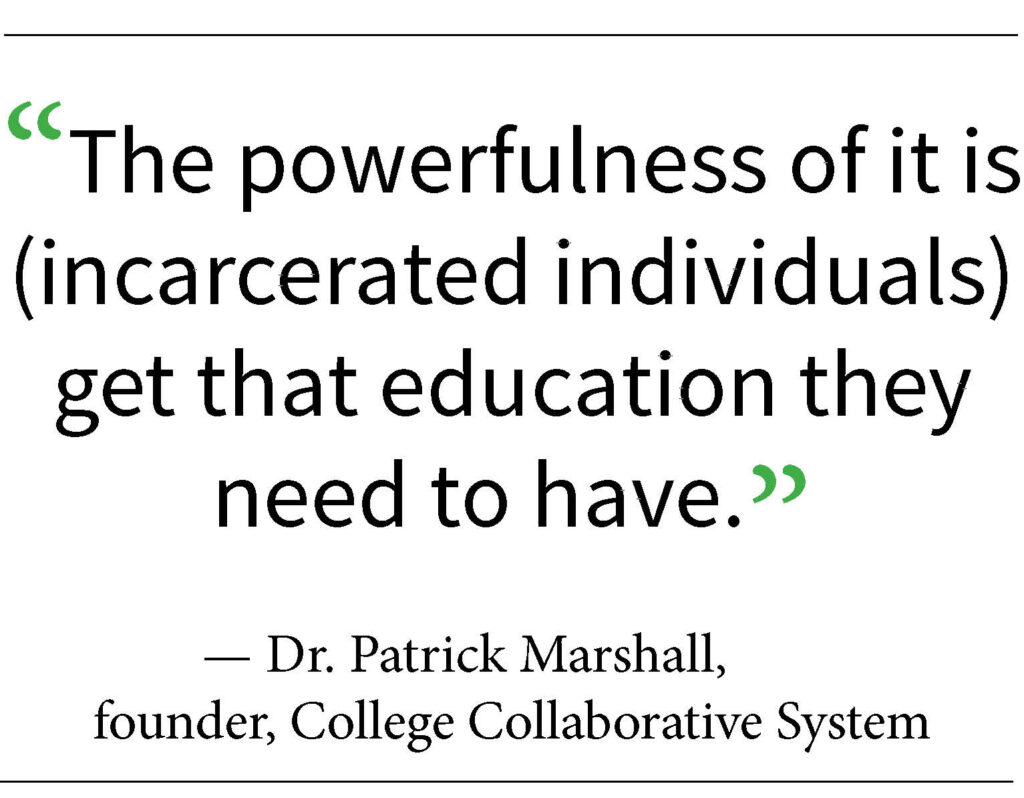

“The powerfulness of it is (incarcerated individuals) get that education they need to have,” he said. “The belief in themselves — to have hope.”

When he first began, Marshall struggled to get his idea off the ground. He started at the bottom of the college and criminal justice system.

He faced a variety of problems, most notably people’s lack of faith in his idea. In contrast, he also had the embrace of supporters who encouraged him.

As he worked his way up the chain of command, he eventually reached the college presidents of various community colleges including Gavilan, Ohlone, San Jose City, and Mission colleges. They supported his idea and gave him the motivation to continue pursuing the dream. As he presented the College Collaborative talk, Marshall credited the college presidents as “change agents.” He views them as his No. 1 supporters in his journey to change the correctional system.

“We couldn’t do this without them,” he said.

He made a memorandum of understanding with colleges to provide rehabilitation training for individuals in jail. Rowena Tomaneng, president of San Jose City College, served as the first one to break the “jurisdiction lines” in signing the MOU, thus seeding the growth of the College Collaborative, Marshall said.

Capt. Gurpreet Gill, a close friend of Marshall an officer he met at a county jail, joined him on stage to present the College Collaborative. Both men felt excited to share with the audience their experiences on how the educational program helps inmates.

Marshall considers Gill his right-hand man in operations.

Marshall considers Gill his right-hand man in operations.

“I have the vision, the ideas, and the design, but he knows how to make it work in a correctional environment,” he said.

The College Collaborative System provides incarcerated individuals with options, opportunity, and hope, Gill said. Before the system, there was no real access to college classes or courses, but CCS made the training possible

Marshall’s system provides opportunities in county jails to learn new skills for jobs upon release. These include auto repair, culinary pathways and veterinary assistance.

“With opportunities came some semblance of hope, hope to pick up a new skill, hope to break the cycle of incarceration and reoffending,” Gill said. “The CCS is truly a transformative system that should be replicated all over our nation. It provides individuals with access to post-secondary options and skills.”

Basic skills including interaction with other people, self-assessment, and being able to communicate effectively are also part of the program, he said. Individuals also learned valuable marketable skills, which provide them with an avenue to grow through culinary, information technology, auto, vet tech, and entrepreneurship pathways to name a few.

Marshall plans to expand the College Collaborative to other California counties. He intends to bring this training to Southern California, including the Los Angeles County jails. If done correctly, he believes it can be an attachment to the court system, giving individuals an alternative to regular prison time.

Marshall built the program to be self-sustaining as long as colleges support it.

“It takes a community, a village to raise a child. It takes a village to have that support for an individual,” he said, referring to the inmates.

He hopes various cities in the county support his program for helping inmates find job skills through community colleges after they leave jail. He especially would appreciate volunteers providing their service at colleges, assisting in the training program.

Marshall feels grateful for all the professors who already teach at jail facilities. It’s their choice to stay and work with the prisoners, he said. With the county’s financial aid, and support from colleges, he sees the potential for a major shift in correctional reform.

He also views the College Collaborative as a way to reduce prejudice within criminal justice systems. Social injustice brought upon incarcerated individuals is often not acknowledged, but through his system, Marshall hopes to shine a light on the discrimination. The spread of information about the system to the public can help encourage more human treatment during incarceration, he said.

“When I look at oppressive barriers that are in place in jail systems and business systems, I want to take down those oppressive barriers,” he said.

Marshall strives to reduce criminal injustice by improving the education of inmates. By training the individuals in academics and job skills, they are less likely to relapse.

Gavilan College president and superintendent, Pedro Avila, said everyone deserves a second chance. And its Higher Aspirations Program in collaboration with Marshall’s system positions the college at the forefront of statewide efforts to reduce recidivism.

“We are already witnessing the program’s success through inspiring stories of students who have graduated, transferred to four-year universities, and become role models for other students with similar backgrounds,” he said. “Their achievements are a testament to the power of education and second chances.”

Daniel Edwards will be a junior at Sobrato High School this fall. He wrote this story with mentorship by publisher Marty Cheek.