Downtown Gilroy vigil draws thousands to show community will not let shootings destroy its spirit

Photo by Marty Cheek

From left: Mildred Torres, Evelyn Torres, Lillyane Sanchez, (holding middle sign) and Yesenya Jaurigue show their pride for their city at the Gilroy Strong vigil held Aug. 1 in downtown.

By Marty Cheek and Robert Airoldi

Santino William Legan’s attack on the Gilroy Garlic Festival visitors lasted for less than a minute. Its impact on the South Valley will last for years.

As the festival prepared to close down Sunday, July 28, the barrage of bullets crackling through the air at 5:41 p.m. transformed visitors’ joy into terror. The 19-year-old gunman randomly shot at the crowd with an assault rifle. His attack resulted in the deaths of Stephen Romero, a 6-year-old boy from San Jose; Keyla Salazar, a 13-year-old girl also of San Jose; and Trevor Irby, 25, of Romulus, NY.

As the festival prepared to close down Sunday, July 28, the barrage of bullets crackling through the air at 5:41 p.m. transformed visitors’ joy into terror. The 19-year-old gunman randomly shot at the crowd with an assault rifle. His attack resulted in the deaths of Stephen Romero, a 6-year-old boy from San Jose; Keyla Salazar, a 13-year-old girl also of San Jose; and Trevor Irby, 25, of Romulus, NY.

Within a minute of the shooting, three Gilroy police officers on patrol returned fire with their handguns, wounding Legan before he took his own life. Their swift action prevented more carnage, said Gilroy Police Chief Scot Smithee at a press conference July 29. The officers are Eric Cryar, 23-years of experience; Hugo Del Moral, 17 years; and Robert Basuino, 13 years.

“I’m angry because this person entered the festival and showed a callous disregard for human life,” said Gilroy Mayor Roland Velasco. “He took the Garlic Festival away from Gilroy. That will always be there now.”

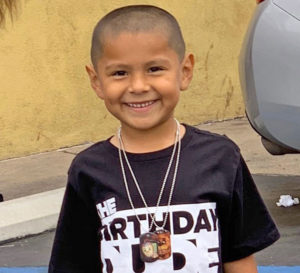

Stephen Romero, age 6

The FBI is treating the shooting as an act of domestic terrorism because Legan had compiled a “target list” that included religious groups, federal buildings and both major political parties. Legan grew up in Gilroy.

Before the attack, he had posted on his Instagram account a message promoting a book titled “Might is Right,” which is considered by some a manifesto of white supremacy.

John F. Bennett, special agent in charge with the San Francisco FBI, told reporters Legan had been “exploring violent ideologies” but declined to give details.

Legan legally purchased the WASR-10 assault rifle (similar to an AK-47) online July 9 from Big Mike’s Gun and Ammo in Fallon, Nev. About 5:40 p.m. on the final day of the festival, he entered the grounds at the northeast corner of Christmas Hill Park by cutting through a perimeter fence along Uvas Creek. In the area near the Vineyard Stage, he opened fire. Sound engineers and members of the band Tin Man performing on stage smelled gunpowder and heard shots. Chaos and screaming erupted as people started running to find a safe place or crouched behind their vendor booths.

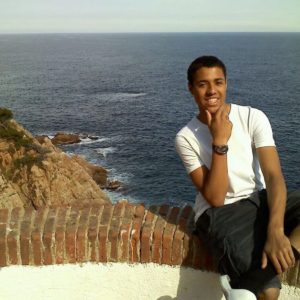

Keyla Salazar

Jack Van Breen, the guitar player, saw the shooter soon after he emerged from the creek and into the festival grounds.

“We just started an encore when I heard ‘pop-pop’ and thought ‘that’s not normal,’” he said. “I looked over my left shoulder and saw the gunman carrying the gun. He started shooting into the dining area. He seemed intent on killing people.”

The band members cleared the stage and hid under it, except for the drummer who scrambled behind the drum kit riser. After officers found them, they directed the performers and other survivors to the beer area where they hid behind beer trucks, before they were led to the Amphitheater Stage.

Victims assisted

Police dispatchers started receiving 911 calls reporting the shooting immediately after the attack started. Audio indicates how the chaos lasted for about 25 minutes as officers tried to secure the scene and called for paramedics to help the injured. Medic helicopters were called in to bring victims to area hospitals.

Trevor Irby

First-responders went into action to assist the victims. A woman identified as “Kim” reported to 911 that she’s a nurse and was assisting a 26-year-old man, shot in the leg and hip. She used an apron as a tourniquet to stop the bleeding. A San Jose Fire Department captain started CPR on Romero who had been shot in the back after fleeing the bounce house he had been playing on. He worked for 15 minutes but was unable to save the child’s life.

Mayor Velasco was on the other side of the grounds when the attack began. When he arrived, he saw paramedics working with the wounded in the initial stages of triage. He helped by taking notes as first-responders gave statistics about each victim. He recalls later taking off the first-aid gloves with blood on them and putting on a clean pair to pick up the gauze and bandages on the ground. That give him time to reflect on the reality of the violence that hot afternoon.

“Shit, this is really happening,” he said, recalling his thoughts. “It was very surreal . . . I want to emphasize that the people of Gilroy did nothing wrong. The Garlic Festival Association did nothing wrong. This is one individual who decided to take human life. I don’t want Gilroy blaming itself.”

Community unites

About 24 hours after the attack, a thousand or so South Valley residents gathered at a candlelight vigil held at the plaza in front of City Hall. Songs were sung and prayers were said. People hugged and cried together. Local artist Nacho Moya displayed a large drawing of a garlic clove over an American flag. The words “Gilroy Strong” expressed the will of the community to refuse to let the mass shooting damage its spirit.

About 24 hours after the attack, a thousand or so South Valley residents gathered at a candlelight vigil held at the plaza in front of City Hall. Songs were sung and prayers were said. People hugged and cried together. Local artist Nacho Moya displayed a large drawing of a garlic clove over an American flag. The words “Gilroy Strong” expressed the will of the community to refuse to let the mass shooting damage its spirit.

At St. Mary Parish Church that Monday evening, every seat was filled with people gathered to pray for peace and for the dead and wounded. Francisco Lopez shared his experience facing terror while selling lemonade at a booth near where the shooting occurred. For years, the booth has raised funds for the St. Mary’s mission to take teenagers to build houses in Tijuana.

When he realized the seriousness of the situation, he dropped to the ground inside the booth and waited until the bullets had stopped.

Photo by Marty Cheek

Poppy Jasper Film Festival Director and Gilroy resident Mattie Scariot and friend Justin Bates, at the Aug. 1 vigil. Bates was wounded in the shooting.

“I felt scared. I didn’t know what was going to happen next,” he said. “When the shooting stopped I called my wife to tell her that I was OK. And I started to look for my kids as everyone was doing.”

How can something like this happen in an otherwise peaceful community? he wondered. He felt sad for the victims and their families and for the senseless violence, he said.

“In the midst of chaos, I saw hope,” he said. “I saw the hand of God on everyone that was helping, including a random family who opened the door of their car and drove my son with another family to their home away from harm’s way. They took care of him until it was safe for me to pick him up.”

Help from near and far

The festival brings in volunteers from Morgan Hill as well as Gilroy schools and nonprofit organizations. About 25 students from Live Oak High School’s Emerald Regime were working during the time of the shooting. Morgan Hill Unified School District provided school buses and drivers during the three days of the festival to shuttle visitors between the parking lot and entrance gate, said Superintendent Steve Betando.

The festival brings in volunteers from Morgan Hill as well as Gilroy schools and nonprofit organizations. About 25 students from Live Oak High School’s Emerald Regime were working during the time of the shooting. Morgan Hill Unified School District provided school buses and drivers during the three days of the festival to shuttle visitors between the parking lot and entrance gate, said Superintendent Steve Betando.

“One of the things the (bus) drivers did was take direction from police,” he said. “But before the police got there, people were running and the bus drivers were loading them to move them out of the area.” The drivers saw the fear in the people’s faces and realized something terrible had happened, he said.

The buses brought people to Gavilan College and other sites for reunification with family and friends.

Gavilan has been a partner with the festival since 1979 when Rudy Melone, then the college’s president, came up with the idea to celebrate Gilroy’s garlic heritage. After the shooting, the campus’s classrooms served as sites to assist people who fled as well as for police to interview witnesses and as an information center for reporters, said Gavilan President Kathleen Rose.

Ron Hannon, dean of Kinesiology & Athletics, organized the college’s staff to assist survivors and police.

“It was surreal,” he said. “As somebody who grew up in this community, we’ve all grown up with the festival as part of our summer activities. And to have something like this happen in your backyard, I’m just at a loss for words.”

At a press conference held the evening of the mass shooting at Gavilan, Brian Bowe, executive director of the Gilroy Garlic Festival, said, “Gilroy is an amazing, tightly-knit community. We are family. We have had the wonderful opportunity to celebrate our family through our Garlic Festival, and for over four decades that festival has been our annual family reunion. It’s such a sad, horribly upsetting circumstance that this happened on the final day of this year’s festival.”

Morgan Hill City Manager Christina Turner, a former Gilroy resident, noted at the Aug. 1 Morgan Hill Chamber of Commerce breakfast that some of the city’s police officers were among the first responders assisting victims and providing security after the mass shooting. She observed that Morgan Hill in June had three people die from gun violence from a former employee at the Ford Store auto dealership.

“We continue to mourn the victims of the Ford Store shooting and pray for their families, friends and all those affected by the tragedy. And now we grieve for the victims of the Garlic Festival shooting and offer our prayers and thoughts to everyone affected by this unspeakable incident. Now more than ever, we can come together and support each other to show our strength and compassion with each other.”

Gilroy businessman Hamdy Abbass had been scheduled to work Sunday at the festival but had to reschedule because something else came up. He had spent Friday and Saturday of the festival volunteering with other Gilroy Rotary Club members at a booth that matches people who need bone marrow transplants with donors.

He recalls standing at the City Hall vigil and thinking about the community’s resilience to face an evil deed with a peaceful gathering. “Gilroy’s small town spirit will not less us stop,” he said. “It makes us much stronger than what we were.”

Abbass said he felt a mix of emotions — depression, sadness and anger — because he considers the Garlic Festival a source of Gilroy pride and the mass shooting put a stain on the event.

“It is something that everyone who works or lives in Gilroy participates in,” he said. “It does so much for the community that I consider it an honor to be a part of it. I grieve for the people who lost their lives. I pray for the injured. And I salute our law enforcement for their quick response. Gilroy is strong. We’ll come back. We’ll get over it.”

Community gathers for vigil

At a vigil held downtown, Aug. 1, more than 2,000 people showed up, many wearing Gilroy Strong T-shirts and carrying home-made signs to show their pride in Garlic City.

Various local, state and federal leaders spoke about the impact of the shooting. Among them was Gilroy City Councilmember Marie Blankley, who described how she was making frozen mimosas as a fundraiser for the Gilroy Rotary Club. Her shifted ended at 5:30 p.m. and she was leaving the park moments before the shooting began. Several of her friends were hit by bullets.

“Our Gilroy police officers on the scene did not hesitate to meet that gunman head on and stopped him within a minute. So many people were in the middle of that chaos and tried to help each other,” she said. “In my 55 years as a Gilroy resident, never have I felt such pride in the whole of our community. The outpouring of love and concern and help from individuals and organizations is a testament to our strength as a community. Gilroy stands strong.”

Velasco, condemning the shooter, said the tragedy will only strengthen the community.

“Please, look around,” he said at Thursday night’s vigil. “Look at this crowd. That bastard did not destroy us. He strengthened our resolve and brought us together like never before.”