For 13 years, religious group has tried to build facility in San Martin

Photo by Marty Cheek

Muslims pray on Friday, Aug. 2, at their temporary mosque — a converted barn — behind a home in San Martin.

By Marty Cheek

South Valley Islamic Center leaders plan to meet with the Santa Clara County Planning Commission Aug. 22 to find out if they can move forward with construction of the Cordoba Center.

The mosque and religious facility has garnered opposition from some San Martin residents concerned about the environmental impact of the project.

SVIC’s members have gone down a long road to build a site for local Muslims to practice their faith. On Friday afternoons, Muslims now meet in a converted San Martin barn that can hold up to 50 people. Located behind the home of a member of this faith community, this small mosque was meant to be a temporary site for two years.

For 13 years, members of SVIC have worked to develop the Cordoba Center. Situated on a 15.8-acre site on Monterey Road a mile or so north of the village of San Martin. Tall poles and cords with flags now show the scale of the structures of this multi-use religious and cultural center.

Photo by Marty Cheek

Karen Musa, Hamdy Abbas and Hina Moheyuddin stand on the property in San Martin on which the South Valley Islamic Community hopes to build a mosque for their congregation of about 100 to 110 families.

Groundbreaking for the project has been held up by delays as residents over the years have expressed various concerns including noise, traffic, the scale of the buildings, and the risk of contamination of the ground water from the Muslim cemetery on the property.

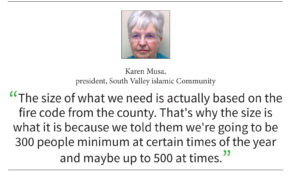

An RV park adjacent to the Cordoba Center land is now undergoing an environmental impact study. That project is not receiving the same level of objections as the Cordoba Center has received, said Karen Musa, president of the SVIC.

An RV park adjacent to the Cordoba Center land is now undergoing an environmental impact study. That project is not receiving the same level of objections as the Cordoba Center has received, said Karen Musa, president of the SVIC.

“That’s going to be high density,” she said. “That’s going to be a lot of people running water and flushing toilets all day long every day, where for us it’s going to be just a few people once a week (on Fridays).”

At the May 23 Planning Commission meeting, based on public comment the county commissioners asked that the SVIC consider scaling down the planned size of the mosque (at 9,000-square-feet) and the multi-use room (at 14,500-square-feet). South of the site, Santa Clara County broke ground June 26 to build a new animal shelter, a facility that will have a footprint of 37,000-square-feet. There was no public objections to the size and environmental concerns of that project.

SVIC’s membership is growing as more Muslims move to the South Valley region. The faith community serves between 100 and 110 families, Musa estimated. The converted barn mosque is too small to safely be used for large gatherings. The limited space for parking is also a challenge, she said.

“The neighbor across the street generously offered his site for parking, which did help,” she said. “But when we have a big group for a big function, we can’t do it because there’s no parking.”

Safety plays an important role in the size of the Cordoba Center. SVIC needs a facility for at least 300 people who will gather for Friday prayer services and holiday events. Muslims need space to move and bow as they pray. And a smaller mosque packed with hundreds of people would be hard to evacuate if there is a safety threat such as a fire, Musa said.

“The size of what we need is actually based on the fire code from the county,” she said. “That’s why the size is what it is because we told them we’re going to be 300 people minimum at certain times of the year and maybe up to 500 at times.”

The facility plans show that all the structures on the site will encompass four percent of the land, she said. The SVIC wants to have natural open space around it, including orchard trees along Monterey to reduce traffic noise.

Convenience for local Muslims to practice their faith is another reason SVIC wants to build the Cordoba Center. The small size of the barn mosque and limited parking restrict the numbers of members who can attend on Friday. Many can’t travel to larger mosques elsewhere because they don’t have the time or transportation to go the longer distances, said Hamdy Abbass, a Gilroy businessman who is a member of SVIC.

“If I want to go pray right now, I have two choices: either to go to Santa Clara or to Monterey,” he said. “It takes me maybe 45 minutes to go to Santa Clara for our Friday prayers, and it might take me two and a half hours to come back. Why should I do that when we have purchased land and have everything here?”

The convenience of a cemetery on the western portion of the Cordoba site was another point of objection. Several nearby residents have said the decay of the corpses has the potential of putting pollutants in the ground water, spoiling their wells. At the May meeting, longtime resident John Beebe expressed his concerns about protecting the safety of his well water. He lives within walking distance of the Cordoba property, he told the officials.

“On my property is a well and we’ve just recovered from a perchlorate spill which pretty much destroyed several wells in this area,” he said. “And we’ve gone through about 25 years of recovery. Twenty-five years. A lot of people in this audience don’t live here. I live here. My water is here. I’m concerned about my water. Now we’re going to be doing all these monitoring wells and testing the water quarterly, which is terrific. But what if? What if we pollute the water? Who’s going to clean it up? That’s my question.”

An environmental report for the project included a letter from Norman Hantzsche, an engineer at Questa Engineering Corp, which studies environmental and water resources. The letter says that Questa reviewed the technical information for the Cordoba Center’s wastewater treatment system used to control nitrates and other chemicals.

“Based on the submitted materials along with our own experience and knowledge of the AdvanTex treatment system, we find that the revised plans for wastewater treatment are suitable for the project and capable of meeting the recommended 20 mg-N/L effluent limitation,” according to the report.

The closest Islamic cemetery is in Livermore, Abbass said.

Other environmental concerns of the project — including noise and lighting and traffic — had no significant impact, according to the EIR.

Land was purchased in 2006 when the project application process was started. The project received unanimous approval of the Santa Clara County Planning Commission and the County Board of Supervisors in 2012, followed by opponents suing the county on grounds that the project would damage the environment. At that stage of the project, SVIC decided to avoid a lengthy legal battle and relinquished its entitlements.

As much as he appreciates their public service, Abbass is uncertain about the planning commission’s reasons for requesting smaller facilities.

“Is it to appease a certain people or certain organization? Or did they just disregard the recommendation of their planning staff because the planning staff gave their recommendation to approve the plan as it was submitted?” he wondered. “Now when you ask us to reduce the size, we abide to have certain square footage per person as part of the use permit. That means that we have to tell half of our members not to show up.”