Finding a place to rent in Silicon Valley is difficult during global pandemic

Photo by Marty Cheek

David Parrott has been living in a rented minivan on the streets of Morgan Hill after a series of unfortunate incidents.

By Marty Cheek

A series of unfortunate events starting with a broken neck and enhanced by the COVID-19 pandemic brought David Parrott, a 50-year-old veteran and father of two, to find himself dwelling in a rented minivan on the streets of Morgan Hill. His story shows how unfortunate circumstances can sidetrack an individual and cause them to end up homeless.

After graduating from Branham High School in San Jose in 1988, at age 18 Parrott joined the U.S. Army with a desire to serve his nation. The military trained the teenager in electronics and as a medical technician sent him to Kuwait during the Gulf War.

After graduating from Branham High School in San Jose in 1988, at age 18 Parrott joined the U.S. Army with a desire to serve his nation. The military trained the teenager in electronics and as a medical technician sent him to Kuwait during the Gulf War.

“When I got out of the military, I got out during the Clinton era,” he said. “Right after the Gulf War, they were downgrading. The Army said you can leave with all the benefits that you’re entitled to.”

Unfortunately, Parrott found he would not receive the benefits of the GI Bill. He had served in the Army for two years and 364 days. If he had left one day later, he would have served a full three years. He would have then been entitled to funds for a higher education.

“I went to apply for the college benefits and they denied it. No one said anything. And that happened to a lot of people,” he recalls. “At that time in my life, I was young and stupid and I said screw — I used bigger words — the military. I never looked back.”

He moved to Southern California and found a job for half the year wildland firefighting with the California Department of Forestry. In the winter and spring, he worked in construction. This period of life lasted three years. He returned to San Jose and worked for the city as a lifeguard at Almaden Lake when it allowed public swimming. He also found work with the city on its anti-graffiti efforts and teaching Red Cross CPR classes for certification.

Photo courtesy David Parrott

David Parrott served in the U.S. Army during the Gulf War.

By 2002, he was married and raising two children (a girl, who is now 22, and a boy, who is now 25). He enjoyed his job teaching CPR with a side gig of teaching hazmat training at the police academy when it was at Gavilan College’s main campus. But he dreamed of becoming a professional firefighter. He went to paramedic school and also the fire training academy at Evergreen Community College through the South Bay Public Safety Consortium. The city of Santa Clara hired him as a reserve firefighter. This put him on the path to eventually being hired full time.

Then life circumstances started a cascade of painful events for Parrott. His wife at that time had a DUI accident. This eventually led to their divorce, and he got full custody of his son and daughter. He found himself juggling jobs as he raised them. In 2007, while working for the city of San Jose, he slipped and fell out of a vehicle at Almaden Lake Park. The accident broke his neck.

“I had to have surgery. It took me two years to recover from it,” he said. “The fire department said I was no longer medically qualified to be a firefighter.”

The pain from the injury and the depression that came from the death of his dream career led him to take methamphetamine and abuse alcohol. Not being able to work because of the neck injury, he became homeless in 2009 and started sleeping in a shelter at night. His ex-wife got full custody of the kids. He refused to seek help from the Department of Veterans Affairs.

“I was saying, woe is me as anyone does when the woe is me happens. It really spun way out of control,” he recalled. “I was looking at maybe going to prison. And the social worker said, ‘What are you doing here? You’re a veteran.’ And I said, ‘The VA screwed me, I don’t want to have anything to do with the VA.’”

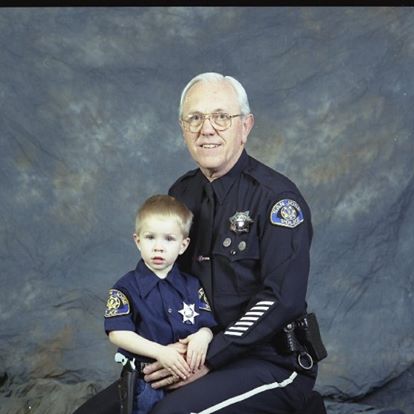

David Parrott as a child with his police officer father.

Photo courtesy David Parrott

Eventually, the law caught up with Parrott. He was arrested on a charge for possession of meth. It was extra painful because his father had been a cop. Time in a jail cell forced him to admit he had an addiction problem. The judge told him, “Hey, we’ve got the VA right here. They can put you in a program and get you well.” Angry at how the military treated him when he left it years ago, he told the judge, ‘Screw the VA.’”

Parrott thought he had reached the bottom of life.

“I gave up,” he said. “I was expecting to go to prison, I really was.”

The judge, however, told him that he had good news and bad news. Parrott was allowed to go home. But home would be the VA. The year 2010 was a turning point in his recovery.

“It’s not the same as the old VA where a lot of people got screwed over. The new VA takes care of people,” he said. “In five months, all my criminal charges were swept away through the VA, those were all dismissed. I was sent to school. I had my kids back. I was back at home.”

The VA provided grants for him to continue his education. In four years, fighting hard against his attention deficit disorder and dyslexia, he earned an associated arts degree. He enrolled in the private school Palo Alto University and earned a bachelor’s degree in social psychology. This was paid for with the help of veterans grants and student loans, which he is still paying.

The VA hired him as a lifeguard to provide recreational therapy assistance. He helped injured veterans to walk again by exercising in swimming pools. This therapy also helped him mend his neck injury.

“I was still in my life where I didn’t get it yet. But the therapy of working with these guys, it was like they were giving back to me,” he said, stifling back the heavy emotions of those memories. “They were kind of my cure.”

“I was still in my life where I didn’t get it yet. But the therapy of working with these guys, it was like they were giving back to me,” he said, stifling back the heavy emotions of those memories. “They were kind of my cure.”

Just as Parrott’s life was turning around, bad luck came again. He started getting sick because the house he was living in under Section 8 was filled with mold. The landlord refused to fix the problem. In September 2019 he moved out because of the health risk.

Silicon Valley can be a hard place to find affordable housing. He started living in a series of hotels, spending his own money. Working full time with the VA, he was still able to afford a motorcycle and a car and a truck. He found shelter for himself and his son and daughter in Saratoga at a home with a sub-house he rented. To help raise extra money, he and his son started a recycling business as a side gig to his full time job. Then the city of Saratoga red-tagged the sub-house they rented because its construction violated codes. At the beginning of March, Parrott and his children again found themselves homeless at a time when the pandemic was growing as a problem, making it nearly impossible to find a place to rent. Parrott and his son started living in hotels. His daughter married a marine and moved to North Carolina with her new husband.

Silicon Valley can be a hard place to find affordable housing. He started living in a series of hotels, spending his own money. Working full time with the VA, he was still able to afford a motorcycle and a car and a truck. He found shelter for himself and his son and daughter in Saratoga at a home with a sub-house he rented. To help raise extra money, he and his son started a recycling business as a side gig to his full time job. Then the city of Saratoga red-tagged the sub-house they rented because its construction violated codes. At the beginning of March, Parrott and his children again found themselves homeless at a time when the pandemic was growing as a problem, making it nearly impossible to find a place to rent. Parrott and his son started living in hotels. His daughter married a marine and moved to North Carolina with her new husband.

Bad luck poured on Parrott. His motorcycle got stolen. His truck was impounded. His car was taken under the lemon law. He couldn’t make it to work reliably at the VA so that impacted his job and revenue.

“Things are spinning out of control left and right and I’m losing things faster than I can hold on to them,” he said of that time.

On the night of April 24 while sleeping in a hotel, a friend of his on PCP went delusional and put a one pound brick of soap into a pillow and started hitting him while he was sleeping, breaking ribs. The attack also injured his head.

“It caused a brain bleed and made me really start to forget things,” he said. “I didn’t know what was what. The head injury caused a lot of confusion. When the head injury happened, it really felt like I was on acid. Everything was a blur, everything was confusion.”

Parrott went from hotel to hotel. In north San Jose, he found himself in a “party hotel” where other people often got loud. The hotel staff warned him to stop making noise but he insisted to them that he was not causing the problem. On Labor Day weekend, he got sick with a temperature of 101. Sleeping late at night, he woke when he heard knocking on the door. Two San Jose police officers told him he had 10 minutes to gather his possessions and get out of the hotel. Parrott told them he was sick but they insisted he leave.

His truck was in the shop being repaired so he rented a minivan. He had taken $4,000 in cash out of his bank account to pay for the truck. Unfortunately, it was in his wallet. In his confused state when the police told him to leave the hotel room, he left it behind. He never recovered the money. He started a GoFundMe account (www.gofundme.com/f/homeless-veteran-again) to raise money to get his truck back.

David Parrott with a fire fighter crew. Photo courtesy David Parrott

“Truly, the police should have done their jobs better to make sure I wasn’t committing a crime, but they didn’t,” Parrott said. “That’s not their fault. They probably deal with that everyday where people claim they didn’t do it.”

He decided to drive to Morgan Hill to seek housing here. “Trying to find a place during a pandemic is really freaking hard,” he said. For several weeks, he and his girlfriend put the seats down in the back of their minivan rental and slept at night illegally parked on streets. Sometimes they were awakened by police officers who politely asked them to move, he said.

Parrott sees many men, women and children facing the difficulties of finding housing in Silicon Valley during the COVID-19 crisis. “There are people who are homeless by not their own fault, but they wind up homeless. It’s hard to get housed in this current environment,” he said. “The pandemic caused me to lose everything really, really quick.”

Life without a source of shelter is difficult, he said.

“It really sucks. It’s very degrading,” Parrott said. “It’s hard to tell somebody you’re staying in your car. It’s hard to go into a hotel and say you need a place for five days because you have nowhere to go. It’s really kind of scary. There’s times at night where I keep a baseball bat in my car as defense because you don’t know who you’re going to run into at night.”

Most homeless people seek empathy and want to get out of their situation.

“Too many times people are judgmental,” he said. “They say, ‘Hey, look at that freeloader. Why are we helping that freeloader?’ They don’t know their whole circumstances when they cast judgment on people. As a society, as people, we need to stop being so judgmental and start being a little more compassionate.”