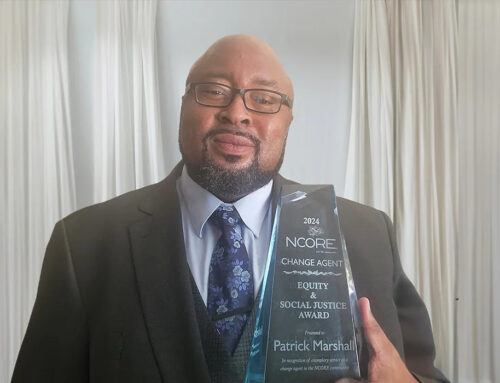

Dignitaries meet Hedy Durlester who was saved, along with others, by the intervention of a Chinese diplomat

![]()

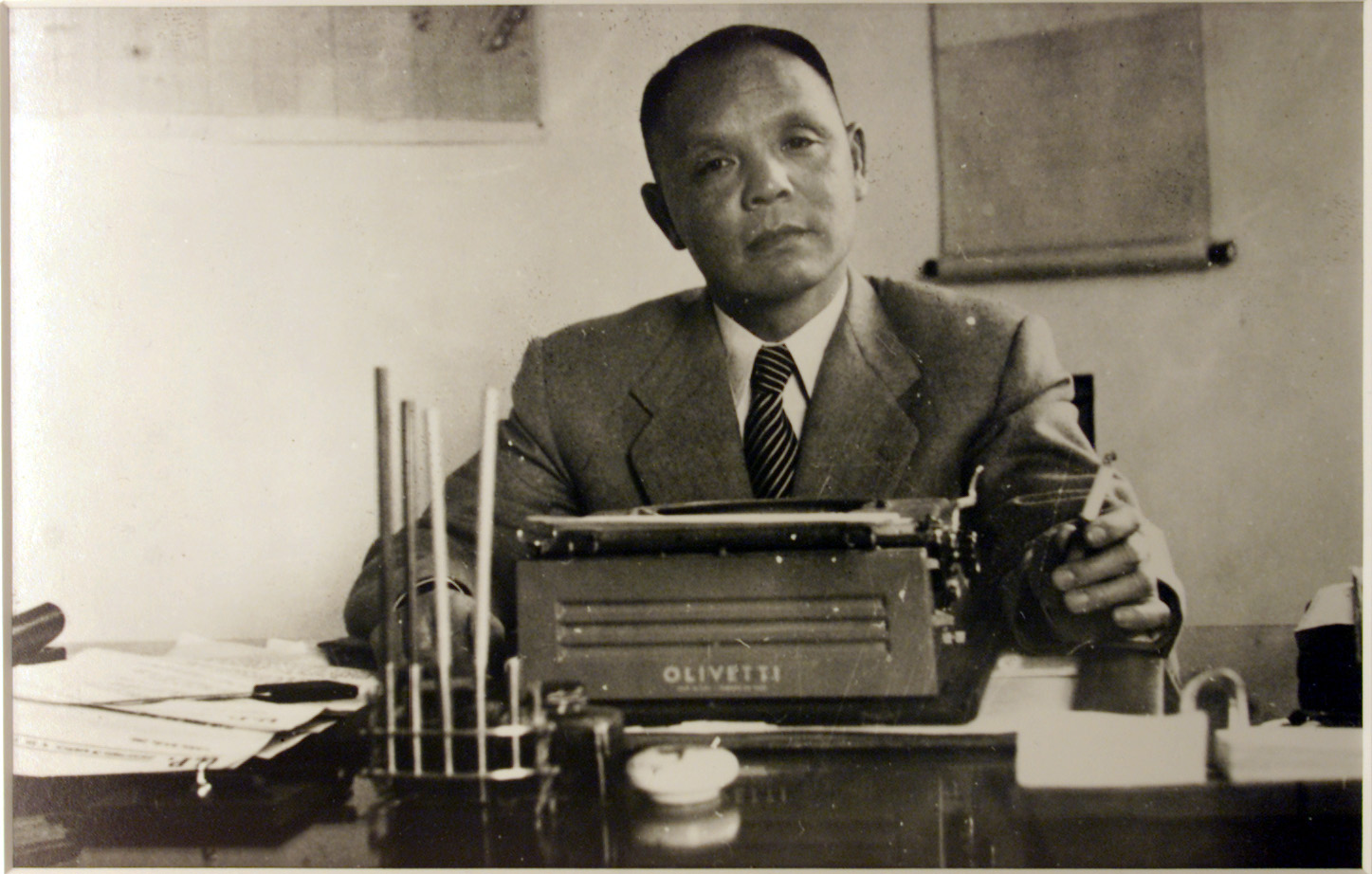

Photo courtesy Ho family

Dr. Feng Shan Ho’s courageous work helped save thousands of Jews from Nazi death camps.

By Calvin Nuttall

From one of humanity’s darkest chapters emerges a story of hope and courage spanning cultures, decades, and continents, finally coming full circle here in the South Valley.

Hedy Durlester, a Holocaust survivor and Morgan Hill resident, was only 3 years old when her family fled from Vienna.

After connecting with the daughter of the diplomat who gave her family their avenue of escape, they pieced together the incredible tale of their flight and the story of a man who leveraged his position to save countless Jews from the camps.

After connecting with the daughter of the diplomat who gave her family their avenue of escape, they pieced together the incredible tale of their flight and the story of a man who leveraged his position to save countless Jews from the camps.

Dr. Feng Shan Ho served as the Chinese consul general in Vienna when the Holocaust came to Austria. Moved by their plight, he worked tirelessly to help thousands of Jews escape the pogrom. In his home city of Yiyang, China, the local museum honors him by maintaining an exhibit and collection documenting his heroism.

Dignitaries from Yiyang came to Morgan Hill to visit Durlester Aug. 17, eager to meet one of the survivors saved by the diplomat’s heroic actions. They exchanged gifts and collected documents and artifacts that Durlester and her family have entrusted to The Yiyang Museum as a part of Ho’s collection.

When Nazi Germany merged with Austria in 1938 in an event known to history as the Anschluss, or “joining,” it precipitated an immediate refugee crisis. Jews desperately sought places to flee. Many nations closed their doors.

Thirty-two western countries including the United States, Canada and Britain held a conference in Evian, France, to discuss the crisis. Thirty-one countries decided against altering their immigration policies to accommodate the influx. As a consequence, Jews in Vienna searched for options.

“So this was the climate that my father saw,” said Manli Ho, Feng Ho’s daughter.

Over the years, to connect the dots of their disparate stories, she worked extensively to collect evidence and testimonies of people he saved.

“He witnessed the Anschluss, witnessed Hitler marching into Vienna in triumph, and then witnessed the immediate persecution of Jews,” she said. “People like Hedy Durlester’s father, Friedrich Heidushka, were arrested and detained. Some of them were sent to the camps, such as Dachau, Buchenwald, etc. At that point, those were labor camps, not yet extermination camps.”

Click HERE to read a version of this story in Mandarin Chinese

Ho felt deeply compelled to help the Jews of Austria when others would not, Manli said.

“Seeing the Jews so doomed, it was only natural to feel deep compassion, and from a humanitarian standpoint, to be impelled to help them,” she recalls him saying.

In doing so, Ho faced a major setback — he was a diplomat without access to his own country. In 1938, much of China, including practically all of its ports, was occupied by the Japanese military. The only way in or out of the country was via Burma or by flying over the Himalayas, a lethal proposition at that time. But there was one exception, somewhere neither the Chinese nor the Japanese had total control — the city of Shanghai.

“After the Chinese were humiliated during the Opium Wars, the foreign powers began to carve up pieces of China,” Ho said. “They basically had no choice but to give it to them. Shanghai was one such place.”

European and American forces forced the Chinese to concede portions of the city to them, resulting in neighborhoods where foreign powers held jurisdiction above Chinese law. This included the French Concession and the International Settlement, controlled jointly by the British and Americans.

“The local Chinese government, including the harbor authorities, fled and left the harbor completely unattended,” Ho said. “When the Japanese moved to take over the port, the foreign powers told them not to, because it would be inconvenient for them. So from 1937 on, the Japanese left the harbor unattended. If you went there, there was no immigration, no customs, nothing. You didn’t have to show any papers. You could just land and get off.”

This lawlessness is what Ho seized on in order to create a loophole he could leverage to help Jews escape from Vienna. At that time, the German government let Jews leave the concentration camps if they could provide proof they would be emigrating from the country, such as an approved entry visa from another nation.

“My father took advantage of this situation by supplying entry visas for an end destination that did not require them,” Ho said. “It was basically a diplomatic sleight of hand. The Nazis’ purpose then was just to get rid of these people, to expel them. When they were let out of the concentration camps, they had to sign an affidavit promising to leave. So that was my father’s scheme.”

Ho provided Shanghai visas to hundreds of Jews with no real intention of them actually arriving there. Rather, the visas served as an initial justification to allow them to leave Germany before departing to their destination of choice. For Durlester’s family, the journey would send them criss-crossing the hemisphere before finally settling into a place where they could weather the war.

“They were on their way to Shanghai, and my grandmother said, ‘I don’t want to go there,’” said Nancy DuBois, Durlester’s daughter. “So they got off the boat in Colombo, Sri Lanka, and somehow my grandfather got the visas switched to go to the Philippines.”

While Durlester and her family waited in the Philippines, thousands of other Jews learned of the Shanghai loophole and escaped Austria and Germany between 1938 and 1941. Many used the strategy to find their way to other eventual destinations, such as Britain, the United States, Palestine, and other havens. More than 18,000 Jews, mostly from Germany, actually did emigrate all the way to Shanghai.

“When my father started using this trick, word caught like wildfire. It put Shanghai on the map as a refuge,” Manli said. “I like to say that he was the architect of the Shanghai Refuge.”

Sometimes called the “Chinese Oskar Schindler,” Ho died in September 1997 in San Francisco at the age of 96. His actions were recognized posthumously by Israel when the organization Yad Vashem awarded Ho Feng-Shan in 2000 the title “Righteous Among the Nations.” According to his wishes, in 2007 he was buried in Yiyang.

Calvin Nuttall is a Morgan Hill-based freelance writer and columnist.