Dec. 21 ceremony is first time a service for deceased homeless is held in Gilroy

![]()

By Calvin Nuttall

Beneath a mournful gray sky, about 50 Gilroy residents gathered on the City Hall lawn. They held flickering candles in a somber memorial for the unhoused members of the community who died in 2023.

The Dec. 21 service sought to call attention to the deaths that often take place out of the public’s sight. The Silicon Valley chapter of the California Homeless Union organized the event in observance of the annual Homeless Persons’ Memorial Day, which takes place on the winter solstice.

The Dec. 21 service sought to call attention to the deaths that often take place out of the public’s sight. The Silicon Valley chapter of the California Homeless Union organized the event in observance of the annual Homeless Persons’ Memorial Day, which takes place on the winter solstice.

“This is a day to remember the people who often aren’t remembered,” said Jan Bernstein Chargin, facilitator at the Gilroy Homeless Task Force and co-founder of PitStop Outreach. “Sometimes, people in their lives didn’t even know they were homeless, and afterward, didn’t know they had passed. So, it is important for us to come together and remember each one.”

Similar ceremonies have taken place across the country since 1990. This year marks the first time the special memorial service has been held in Gilroy. For that reason, the memorial also honored several people who had died in years past, in addition to those of 2023.

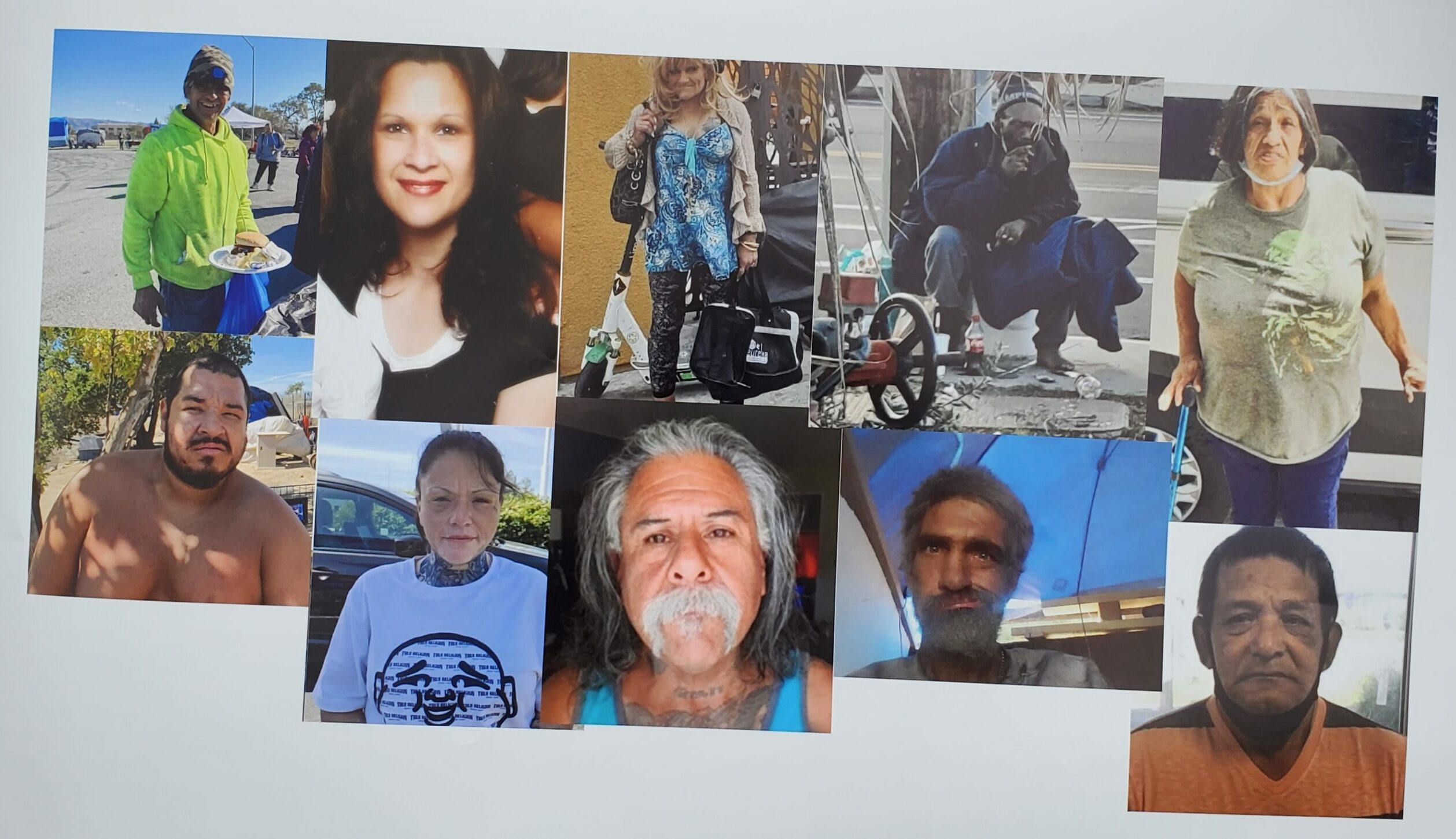

Arrayed across the City Hall lawn, 20 imitation “tombstones” displayed the following names: Jorge Aguero, Alejandro “Mono” Becerra Jr., David Boyer, William Bryant Bretherlok III, Raul Ceja, Emily Faus, Alejandro Flores, Delores Gracia, Abraham Gonzales, Thomas McManus Jr., Michael Meyer Jr., Christopher Mueller, George Montes, Nathaniel Ortiz, Xaniyah Perex, Daniella Pierceall, Ysidro Renteria, Matthew Richardson, Alyssa Salazar, and Kelly Tasker.

“Every person has a story,” Chargin said. “The only generalization you can make about these people is that they didn’t have a place to live that worked for them.”

In October, Alyssa Salazar was murdered by her ex-boyfriend Ivan Escobedo.

“She had been seeking aid from a lot of different agencies, but unfortunately she fell through the cracks,” said Angelina Valverde, South County Compassion Center operation director. “It is a race against time to save these lives. Their voices should be uplifted. They were all special souls, and I am blessed to be able to work with them and share a lot of their stories.”

Emily Faus, also known as “Jupiter,” died in August. Her mother, Terri Faus, remembers her as a smart, funny, and beautiful woman who suffered from mental illness.

“The most frustrating thing for us was that we could not help her,” Terri said. “Because she was a grown adult, we could not get her the help she needed because she refused.”

Often, homelessness and former incarceration go hand-in-hand. According to research by the nonprofit Prison Policy Initiative, formerly incarcerated people are almost 10 times more likely to be homeless than the general public. That was the case for Alejandro “Mono” Becerra Jr.

“He didn’t have a good start to the beginning of his life,” said Graham Melville, a member of PitStop Outreach who has worked with Gilroy’s unhoused.

“When I first used to go out there, he wouldn’t make eye contact with me. He walked the other way.”

Becerra found himself in prison more than once during this time, Melville said. As time went on, however, his outlook began to change.

“Then, he was smiling,” Melville said. “His partner told me, ‘He’s going to turn his life around.’ And he really tried. He was brave, he even started quoting Bible verses to me. He wanted to get out of there. But when they are in that situation, it’s so hard for them to get out.”

For the most vulnerable members of the population, finding housing is a matter of life or death. The life expectancy of unhoused people in Gilroy is only 53 years, compared to 78 for the general population. Unhoused people are exposed to higher risk of death from exposure, violence, and substance-related causes, but the leading cause of death is less obvious.

“Most people who don’t do the work that we do would guess that it was drugs and alcohol — it’s not, not by a long stretch,” said Tim Davis, executive director of the South County Compassion Center. “The number one cause of death for the vast majority of these people was undiagnosed and untreated medical conditions.”

Organizations like the South County Compassion Center do what they can to help members of the unhoused population to find and qualify for housing, Chargin said, but the very limited supply forces them to heavily triage applicants.

“One size doesn’t fit all for housing or for services,” she said.

In several cases, applicants had already been approved for housing when they died, but the organizations assisting them weren’t able to find them in time. In other cases, they were able to get their applicants into housing, but the damage was already done. They died shortly afterward.

“It’s a race against time,” Chargin said. “They’re out there exposed to the dangers, and every day is an exposure to that possibly deadly danger.”

The availability of low-income housing in the Bay Area is far below its demand. According to the National Low Income Housing Coalition, there are only 30 available affordable housing units for every 100 extremely low-income households, defined as those making less than 50 percent of the area median income.

The availability of low-income housing in the Bay Area is far below its demand. According to the National Low Income Housing Coalition, there are only 30 available affordable housing units for every 100 extremely low-income households, defined as those making less than 50 percent of the area median income.

“With the average life expectancy declining, and there not being an adequate supply of low-income housing here in Gilroy, we are sentencing people to death,” Davis said.

Tristia Bauman is a civil rights attorney who serves on the board of directors at the South County Compassion Center. She is also director attorney of housing at the Law Foundation of Silicon Valley. In her work with the unhoused, she routinely hears about ways in which they are abused and victimized.

“These people on the street are our neighbors,” she said. “We can show them we care. We can look inside ourselves and check our own biases, and do that every day and encourage the people who we love to do that as well. That is how we create change.”

Calvin Nuttall is a Morgan Hill-based freelance reporter.