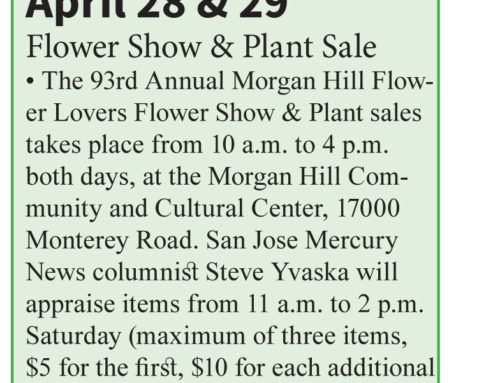

Published in the June 11-27, 2014 issue of Morgan Hill Life

Photo courtesy Lawson Sakai

Lawson Sakai in his U.S. Army uniform circa 1944.

When we learned from Bob Hunt, co-chair with his wife Maureen Hunt of the Morgan Hill Independence Day Parade, that Morgan Hill veteran Lawson Sakai will serve as this year’s July 4th parade grand marshal, we heartily applauded the choice. Sakai’s story is a demonstration of all that is the best about the American character.

Sakai is a modest man who at first was reluctant to take on the starring role in our community parade. He is also a man of honor. During World War II he fought in the legendary 442 Regimental Combat Team, a battalion made up of Japanese-American soldiers who stormed Italy and France and suffered the highest casualty record of any unit in American military history. Sakai and his band of brothers participated in the liberation of French city of Bruyeres as well as the rescue of the Lost Battalion trapped behind enemy lines, an action in which he was seriously injured.

Sakai was born in Los Angeles on Oct. 27, 1923. The day after the attack on Pearl Harbor, the young man attempted to enlist in the U.S. Army but he was rejected because the American government classified him as an “enemy alien.” With the internment of more than 127,000 American citizens of Japanese ancestry that began after President Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 in early 1942, Sakai’s family evacuated to Colorado. In March 1943 the American military, in desperate need of fighting men, opened up enlistment to Japanese Americans to serve in a segregated unit. Immediately, Sakai volunteered for the 442nd. The unit reached Europe in May 1944 and Sakai served there until November 1945.

While fighting for the freedom of Europeans enslaved under Nazi tyranny, Sakai was wounded four times. He received a Bronze Star, a Purple Heart and a Combat Infantryman Badge. He was discharged from the army in December 1945. He still stays active in 442nd reunions.

World War II was called by Chicago journalist Studs Terkel “the Good War” because Americans joined together to fight for freedom for people in Asia, Africa and Europe. No doubt our nation saw a strong unity during the war as we came together for a common goal. But the dark side of our human nature was also revealed in how we treated our fellow Americans, those of Japanese ancestry, as we put many of these families behind barbed-wire fences.

One 23-year-old Japanese American, Fred Korematsu, brought to the Supreme Court a case against the U.S. government’s relocation action. The Supreme Court justices ruled that Executive Order 9066 was justified as a wartime necessity. Forty years later, documentation discovered by University of California, San Diego professor Peter Irons provided evidence that Charles Fahy, the Solicitor General of the United States who argued for the government before the Supreme Court against Korematsu, had deliberately suppressed FBI and military intelligence reports which concluded that citizens of Japanese-American ancestry posed no threat to national security.

As demonstrated by the internment camps during World War II, American history has its ugly side. That fact is something that should be taught in our schools so that future leaders will not repeat the mistakes past leaders have made. But American history also has a side we can all feel pride in with the actions of individuals who volunteer to fight for freedom – even the freedom of people in faraway countries. Many of these men have too often paid the ultimate price in the sacrifice of their lives on the altar of liberty.

Lawson Sakai’s service in the American military – fighting for freedom in the 442nd while that same military took away the freedoms of many of his friends and relatives – is a shining example of our American trait to do the right thing in dark times. When you see him ride through Morgan Hill streets in the parade this Fourth of July, give him a salute as a thank you for what he and other Japanese-American soldiers did in Europe.