Surge of water results in Coyote Creek levee break, closing U.S. 101 and forcing San Jose evacuations

Published in the March 1 – 14, 2017 issue of Morgan Hill Life

Photo By Marty Cheek — For the first time in more than a decade, Anderson Dam spilled.

By Marty Cheek

If it’s not a drought, it’s a deluge. After seven years of minimal rain for California, a powerful atmospheric river pummeled Santa Clara County over several days last month, filling reservoirs and turning streets into Venetian canals.

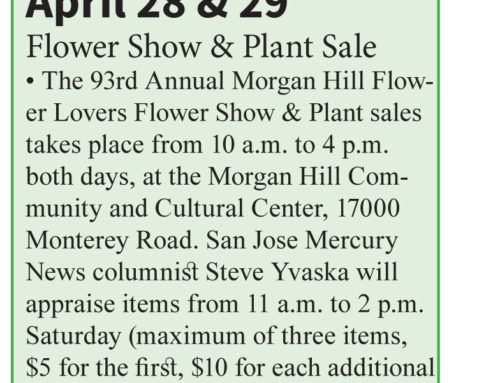

Hundreds of residents headed to Anderson Reservoir the weekend of Feb. 18 and 19 to gaze at the spectacle of a lake filled to capacity. Until late last year, the reservoir had been about half full.

But with record rainfall in January and February the reservoir has continued to fill despite water being released from an outlet pipe since Feb. 9. And with the recent storms, the reservoir — which hasn’t spilled since 2006 — crested, creating a spectacle that led to downstream flooding.

On lookers stood in front of a miniature Niagara Falls at the bottom of the spillway and took photos of themselves as the heavy mist flew over them.

People also stood behind the fence next to the outlet pipe at the bottom of Anderson Dam, snapping selfies as behind them thousands of gallons of water per minute were released, the roar of the high-pressure jet screaming in their ears. Among them were Morgan Hill resident Mike Gallagher and his daughters Kiera Gallagher, 9, a Nordstrom Elementary School student, and Kourtney Gallagher, 5, a Charter School of Morgan Hill student.

“Well… it’s a lot of water. The water looks like caramel… like a caramel river,” Kiera said, describing the scene.

“People want to look at the splashes,” Kourtney explained why so many people came to the dam that Saturday.

The water from Anderson Reservoir cascades over spillway with Morgan Hill homes in foreground.

Photo by Marty Cheek

Mike said he had never seen such a major traffic jam of cars along Cochrane Road bringing people to experience the water wonder.

“It’s just an awesome sight with the spillway going,” Mike said. “I’ve never seen anything like this in the 17 years that I’ve lived here. It’s like Mother Nature has gone kind of crazy.”

The several weeks of seemingly non-stop rain that filled Anderson Reservoir to full capacity caused the water to peak and tumble over the dam’s spillway at 7 a.m. Tuesday Feb. 21. The intense power of 22,400 gallons per second suddenly filling the Coyote Canal caused a levee north of Cochrane Road to fail. The resulting flood hit northbound U.S. 101, stopping vehicles. The resulting freeway gridlock during the morning commute reached to Gilroy and farther south.

The significant flooding in the regions of the South Valley last week helped to highlight the importance of managing our water resources and the infrastructures used by the Santa Clara Valley Water District to prevent flooding and save lives. Many residents considered the stability of Anderson Dam as they watched the news about the Oroville Dam, at 770 feet the tallest dam in the United States. That dam’s spillway in early February suffered significant damage from floodwater, forcing the evacuation of more than 180,000 people living downstream.

Anderson Dam is a 235-foot tall earthen structure that holds 90,000 acre feet of water when its reservoir is full. That’s more than the other nine reservoirs in Santa Clara County combined. An average California household uses between one-half and one acre-foot of water per year for indoor and outdoor use.

On lookers take photos of water rushing out of outlet pipe at bottom of Anderson Dam.

Photo by Marty Cheek

Anderson Dam sits about one mile west of the Calaveras Fault. In January 2009, a seismic study showed that if a maximum credible earthquake of 7.2 magnitude should hit in the vicinity of the reservoir, the top of the dam could slump by 20 to 25 feet. If the reservoir was full, the slump could result in water cascading down the dam embankment, which could cause dam failure. A 30-foot high wall of water would flood Morgan Hill and run towards both Gilroy and San Jose. That’s why, for the past five years, the district has maintained a restricted level of water (about 54 percent full) with the maximum water elevation about 55 feet below the dam crest.

What are the chances of a geologic-related flooding event actually happening?

“Probably never,” said John Varela, chair of the water district board. “Unless Mother Nature in addition to this deluge that we’ve been receiving decides at the same time to unleash a major, major earthquake right on target with point zero being the dam. That raises some concerns in the region, of course, and we’re really doing the best we can to monitor the water. We’ve got to keep it at a certain level. We can’t keep the dam full. You’re damned if you do and damned if you don’t.”

The water district has been preparing for a seismic retrofit of Anderson Dam to attain long-term reliability for a critical component of the county’s local water supply, and provide for public health and safety. The cost of the project was originally estimated at $200 million. In December, the district reported that more geotechnical analysis indicated considerably more work than had originally been estimated would need to be done to safeguard the dam. When Anderson Dam was constructed in 1950, it had been built on alluvial deposits. This soil could liquefy during an earthquake. As a result, the experts recommended removing nearly the entire dam and rebuilding it — at an estimated cost of $400 million. Construction is anticipated to begin in 2020, with completion planned for 2023–2024.

“When these studies were implemented, the information we had on hand was based on the seismic findings that were on the lower dam surface,” Varela said. “A year ago there were additional studies that found seismic faults at the base of the dam itself, which FEMA and the state of California said we have to re-evaluate the assessment of the seismic occurrence that could happen, the intensity of what they are and the total outcome… (Liquefaction) would compromise the entire dam and we would have flooding north to San Jose and south to Gilroy — an estimated level of a 20-foot tide to a 30-foot tide. That’s an extreme example of what could happen.”

The money for the project has already been allocated, he said. Most of it will come from the district’s water rate revenues. Approximately $60 million will be reimbursed from the Safe Clean Water Program, the Measure B parcel tax that voters approved in 2012.

In the meantime, the district is working to lower the reservoir’s level.

“We’re at capacity now, so that’s why the water is spilling, so we have to keep the levels down 20 to 25 feet below the spillway,” Varela said. “The reason why you see the water spewing out of the pipe is that we’re trying to bring the water down to that level.”

The county’s other reservoirs are safe from earthquake disaster. Although many reached capacity from this winter’s series of storm, only Uvas Reservoir posed a problem. Uvas is spilling into the southern portions of the county which is affecting lower lying areas of Gilroy along Miller Avenue, Varela said.

Despite the intensity of recent rains, Varela encourages residents of Morgan Hill, San Martin and Gilroy to continue their water conservation actions.

“Many people are saying that it looks like we’re out of the drought,” he said. “Well, we at the water district don’t consider ourselves out of the drought that we’ve been in for almost the past seven years until we know what our ground water [level] is, that our aquifers are full. That is our primary water source throughout the valley. We’re blessed with water that comes from Mother Nature. But we can only capture so much of it because we don’t have the storage capacity.”