In the deer family, elk are second in size only to moose

By Mike Monroe

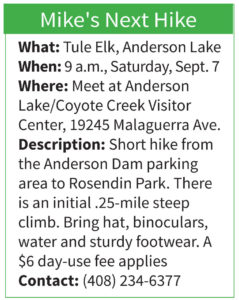

One of the true success stories of bringing an animal species back from the brink of extinction has to be that of the tule elk. Anderson Lake’s senior ranger, Brian Christensen, has generously offered to guide our walk and share his expertise regarding our local tule elk herd which resides nearby along the eastern shoreline and uplands of Anderson Lake.

One of the true success stories of bringing an animal species back from the brink of extinction has to be that of the tule elk. Anderson Lake’s senior ranger, Brian Christensen, has generously offered to guide our walk and share his expertise regarding our local tule elk herd which resides nearby along the eastern shoreline and uplands of Anderson Lake.

Brian suggested that an early September outing would be an opportune time to see the elk using binoculars, and also to hear them as the males will be bellowing (some say “bugling”) their intentions at this peak time of the rut, or breeding season.

The tule elk are the smallest of California’s three elk subspecies with the male (bull) elk weighing between 450 and 500 pounds. Rocky Mountain elk and Roosevelt elk are larger and range throughout the western United States, while the tule elk are located primarily in grasslands and woodlands of Central California.

In the deer family, elk are second in size only to moose. Still elk are California’s largest land mammal. For tule elk, mountain lion and coyote are its primary predators as the grizzly bear population was wiped out by 1924.

Geographically, the eastern foothills of the Santa Clara Valley are part of the Mt. Hamilton Range. Anderson Lake and its older sibling, Coyote Lake, were developed when Coyote Creek was impounded to store water for the thirsty farmland and residents of the valley. The range extends from Mt. Diablo in the north, eastward to Interstate 5 and south to Pacheco Pass. Much of the land is rugged with a few large cattle ranches and a very small population as compared to the neighboring Silicon Valley.

With Henry Coe State Park serving as the anchor (the initial 12,500 acres were donated in the early 1950s by Sada Coe) the open space acreage preserved now totals more than 400,000 acres. A number of public and private agencies, as well as landowners like the Hewlett and Packard families, followed the lead of The Nature Conservancy to create this immense habitat area known as the Mt. Hamilton Project.

Certainly the native Ohlone peoples did hunt tule elk for thousands of years using the meat for nourishment, hides for clothing, and antlers for tools. But their impact on the elk population was negligible and it is estimated that the number of elk prior to the Gold Rush was about 500,000 animals. Soon after the flood of prospectors and settlers arrived the elk herds were decimated by market hunters providing food for the miners, leather and tallow. Within a 25-year period, tule elk were almost completely killed off, compelling the California Legislature to ban elk hunting in 1873. At that time, it was thought the elk were extinct.

Enter Henry Miller, the owner of the Miller and Lux cattle empire and local citizen of Gilroy and Mt. Madonna. He knew that there had been historic tule elk herds in Kern County especially in the proximity of Tulare Lake (named for its tule reed marshlands). His company was in the process of reclaiming the land for pasture and farming by channeling the water flows of the annual Sierra runoff. It was in 1874 that the first pair of elk were discovered by Miller’s cowboys. Eventually about a dozen animals were captured and placed into a 600-acre “preserve.” By 1895, there was a small herd of 28 surviving tule elk which formed the nucleus of today’s estimated 5,700 animals. Prior to his death in 1916 Miller requested that the state relocate the animals and by 1932 an official tule elk sanctuary of 953 fenced acres consisting of 140 elk was created. Unfortunately for the elk, water diversions and illness led to a population decline and in 1954 only 41 elk were remaining.

Thanks to the concerted efforts of California State Parks, the California Department of Fish and Wildlife, federal agencies such as the Forest Service and the Bureau of Land Management beginning in the 1970s the elk numbers did rebound. Through relocations and the establishment of more than 20 preserves, such as the Mt. Hamilton Project, the elk population is no longer in danger although it will never reach its historic levels because of the permanent loss of habitat landscapes. A relocation effort in February of this year utilized helicopters to move the blindfolded and mildly sedated elk to ensure that population levels are maintained in balance at particular preserves.

Please join Ranger Brian Christensen and me for our walk on the slopes of Rosedin Park with the intention of spotting and listening to the elk across the lake. Brian will probably demonstrate his ability to call the elk — but I will not. Keep on sauntering!

Mike Monroe coordinates local discovery outings to fun and friendly places like wineries, parks, museums in the Valley of Heart’s Delight. Visit thevalleyofheartsdelight.org.