Story set at Gilroy Library tells tale of a lost child and a misunderstanding

![]()

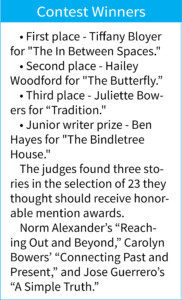

Editor’s note: The following is the first-place winner of Life Media Group’s 2021 short story writing contest. The theme of the contest was “Connecting in the South Valley.” Gilroy resident Tiffany Oaks Bloyer received a prize of $1,000 for her entry.

The In Between Spaces

By Tiffany Oaks Bloyer

The birch tree branches dance and shimmy in the wind. Through the car window, it appears as if they are moving in time to the base and thump of Creedence singing “Heard it Through the Grapevine.” She heard it for the first time in high school — when rumors were on the menu as often as the lumpy piles of mac and cheese. By the time third period rolled around, one’s world could be crushed by the grapevine that snaked its way through the hallways of the school.

The wrong thing spoken from the right person could take you down when you were young. Why do we let the words of people who don’t matter hurt us, she wondered? She couldn’t answer that any more now than she could have at fifteen.

The wrong thing spoken from the right person could take you down when you were young. Why do we let the words of people who don’t matter hurt us, she wondered? She couldn’t answer that any more now than she could have at fifteen.

She remembered how it felt spinning the combination on her locker in the hallway and listening to the burbly river of gossip that flowed in and around and behind her as students reluctantly shuffled toward their next classes. Back then, she had lost herself for a time after some cruel gossip had slithered its way along that grapevine. She had been doubled over by the sucker-punch of being betrayed by a friend and a boy. Then, a string of cruel rumors encircled her like the white chalk at a crime scene. By the time she had recovered and regained her footing, she lost half a year, was failing three classes, and was considered to be a social liability by most of her friends.

Now, she waits patiently for her 17-year-old to find the book he needs from the library and come back to her. She had found his progress report crumpled in the pocket of a pair of jeans. This first semester of his senior year had been an unending litany of disappointments for him. It wasn’t just the grades, but the struggle to find his place and rhythm. Then, there was the crushing shyness that blanketed him at times like a fog rolling in off the coast.

She sits in her car with the window open just enough to feel the morning chill and hear the birds chattering and planning their days as they flit in the trees that line Gilroy’s library walkway. She no longer lives in her hometown, but she thinks Gilroy has that same small town feel. She sits, now, waiting and watching from the parking space near the entrance of the library. The doors glide open and closed, eager to welcome anyone who enters their range.

A man in a dusty army jacket with frayed cuffs and stains sits on the ground, legs outstretched as he leans against the wall of the building near the entrance. His hair is brown with streaks of peppery gray and his face is ashy and stubbled with hair growth. Beside him sits a small dog, who is mostly beige with random brownish spots here and there. She thinks, with a smile, this makes him look a bit like an oatmeal cookie with legs.

A man in a dusty army jacket with frayed cuffs and stains sits on the ground, legs outstretched as he leans against the wall of the building near the entrance. His hair is brown with streaks of peppery gray and his face is ashy and stubbled with hair growth. Beside him sits a small dog, who is mostly beige with random brownish spots here and there. She thinks, with a smile, this makes him look a bit like an oatmeal cookie with legs.

Moms with various collections of children in tow begin to arrive for the 10 a.m. storytime. Most clutch steaming coffees in one hand and phones in the other as their tiny offspring circle around them, quacking and chittering or clinging to the edges of strollers. Many have parked on the east side lot; and as they approach the man and his dog, there is a visceral, often physical response. Some steer their prams in wide sweeping arcs around him. Others seem to grip tighter to their toddlers’ hands, pulling them close while simultaneously wrinkling up their faces as if they had just tasted something quite bitter. Tail quivering with delight, the little dog sits up as each child passes, but then drops his muzzle down on his front paws with the tiniest of whimpers as each little one walks by without a glance.

Finally, the doors sweep open and her son comes out slouching, sullen and beaten down. He slides into the seat beside her. They sit there for a time in silence, and then the next song begins to play softly. She wants to tell him that this time will pass. Whatever his “grapevine” or “chalk outline” is that has unmoored him this year, she doesn’t need to know the details. She just wants him to know that it will get easier, even though in many ways she knows that is a lie. She wants it to be true for him. She wants to tell him that there is a big, wide, beautiful forest out there. He needs to be patient until his eyes and heart can focus past the single tree that has been in front of him, blocking his vision for the past few months. She is thinking all of this as the music plays and then slowly finds her words and begins to speak. At first, he stiffens, gearing himself up for a lecture, but then he lets out his breath as she begins to speak.

“I told you once that you should try to always lead with your heart. I still think that is solid stuff, but I also want you to have your freedom. That means freedom to be what and who you want to be. It means feeling the way you want to feel. Don’t let someone else decide that for you, especially not me or dad or your friends. Don’t give that power away. OK? It’s yours. Hold tight to it. Even if you can’t see your next steps clearly right now, that’s OK. Just don’t let anyone else choose your path,” she says softly.

“I told you once that you should try to always lead with your heart. I still think that is solid stuff, but I also want you to have your freedom. That means freedom to be what and who you want to be. It means feeling the way you want to feel. Don’t let someone else decide that for you, especially not me or dad or your friends. Don’t give that power away. OK? It’s yours. Hold tight to it. Even if you can’t see your next steps clearly right now, that’s OK. Just don’t let anyone else choose your path,” she says softly.

“K,” he whispers.

“Remember when we used to float on rafts at Coyote Lake? I would tie mine to yours so that you wouldn’t float off and get lost. Well, I want us both floating on our own rafts, but that doesn’t mean I won’t be here for you. I will always be here for you. You need your own life, your own spaces, your own friends. But, I want you to know that I will always be there in those hard places, those in between spaces when you feel you can’t move forward or step backward either . . . I will be there.”

A security guard rushes out, morning sun and long shadows playing across the sidewalk and over his shiny black shoes, as he presses his mouth to a walkie-talkie and speaks. Through the car window, the boy and his mother can just make out the details of the frenetic scene unfolding. One of the toddlers has gone missing from the 10 a.m. storytime. Panic crackles in the air like electricity, snapping and popping from a live wire. In the shuffle of movement and eerie calm chaos of the next few moments, no one seems to have noticed the tattered rucksack and small tin bowl filled with water that had been left unattended where the man and his dog were just moments before.

From in the car, the boy and his mother see this just as Creedence shifts to a new song. Softly, but with that beautiful high sweet Les Paul guitar riff, Fogerty begins to sing “Up Around the Bend.” They glance at each other for only the briefest moment, and then her boy points toward the east corner of the building with a smile slowly filling his whole face. Three shadows curve around the bend of the building, tall and delicate as paper dolls, one tall, one tiny, and one four-legged. On the heels of the shadows comes the man and the dog, and between them a little girl. She can’t be more than four, with caramel-colored curls that glint in the sun as she takes little half-hops between the other two. She is holding tightly to the man’s calloused hand and swinging it ever so slightly. Her face tilts up toward his as she explains something indiscernible with a toothy grin and shiny bright eyes.

“Oh, really?” says the man, earnestly.

As they reach the security guard, the details pour out, mostly from the little girl.

“I didn’t like the thtory, it was thcary. I went to look for birdeeth out-thide. Joe here,” at which point she pointed to Joe and giggles, “told me he and Arlo thaw me walk patht him and got worried, tho they jutht came along on my walk with me.”

She reaches down and rubs Arlo between the ears.

“You’re a good boy, Arlo. A thweet boy,” she croons.

It is then that the mother comes racing out of the library doors like a storm coming onto shore from the ocean, picking up all the worry and torrential fears and swells of not just this moment, but the never-ending what-ifs that fill the hearts of all parents. She comes ashore and lands like a fury; she takes in the scene and sees the man in his filthy tattered clothes. His dusty and bruised hands still hold onto her child, and something in her splinters and breaks apart. She hears someone screaming in the distance as though from far away and underwater. She thinks it is her own voice, but she cannot stop it.

From the car the woman and her son watch as the young mother’s face shifts, almost changing colors as it slides from fear to rage when she sees the man with her child. She is screaming at him, and as she lunges at both, the man steps back and the girl begins to cry.

The young mother has dropped her purse, but her phone is still clenched in her hand, fingers blue-white as they hold fiercely to the edges. The guard steps into the center, takes a breath, and begins to calm the storm. The young mother, shaking, kneels on the ground, empty and deflated as a morning-after party balloon. Her girl comes slowly to her and begins to stroke her hair.

“It’th OK, Mommy. Joe and Arlo were being kind. You always tell me how ‘portant that ith.”

“Yes, baby,” she says breathlessly, but her voice is dull and flat. “You’re . . . right.”

The girl skips back to Joe and Arlo and gives them both one last hug, as a barely forming crowd begins to dissolve. From the car the woman and her son are just listening to the last chorus of “Up Around the Bend.” The mom looks at her boy, so old now, How did we get here so fast? She smiles with all the love she’d ever had or ever would have.

“You ready for whatever comes next?” she says with a grin.

They can hear the birds bantering in the low branches that cast lacy shadows across the windshield. Laying gently over that are sounds of little voices, an orchestra of slightly off-key instruments played by beginners with absolutely no direction. Then, over that, the hum of older voices murmuring spectacular nothings to one another to fill the void.

During it all, deep in the in between spaces, during a moment of sweet silence, the boy replies in a whisper, “Sure.”